All,

I hope you enjoyed the ninth week issue from March 28-April 3, 2015 of Volume 1, Number 2 of SOUND PROJECTIONS, the online quarterly music magazine which featured the outstanding trumpet player, jazz and film composer, arranger, orchestrator, ensemble leader, teacher TERENCE BLANCHARD (b. March 13, 1962). The tenth week issue of this volume of the quarterly begins TODAY on Saturday, April 4, 2015 @10AM PST which is @1PM EST.

The featured artist for this week (April 4-April 10,

2015) is the legendary, iconic and innovative singer, songwriter,

ensemble leader BILLIE HOLIDAY (1915-1959). In recognition and deep

appreciation of Ms. Holiday's extraordinary life and career we celebrate

the powerful ongoing legacy of one of the preeminent artists of the

20th century. So please enjoy this week’s featured musical artist in

SOUND PROJECTIONS, the online quarterly music magazine and please pass

the word to your friends, colleagues, comrades, and associates that the

magazine is now up and running at the following site. Please click on

the link below:

Thanks. For further important details please read below…

Kofi

Sound Projections

A sonic exploration and tonal analysis of contemporary creative music

in a myriad of improvisational/composed settings, textures, and

expressions.

Welcome to Sound Projections

I'm your host

Kofi Natambu. This online magazine features the very best in

contemporary creative music in this creative timezone NOW (the one we're

living in) as well as that of the historical past. The purpose is to

openly explore, examine, investigate, reflect on, studiously critique,

and take opulent pleasure in the sonic and aural dimensions of human

experience known and identified to us as MUSIC. I'm also interested in

critically examining the wide range of ideas and opinions that govern

our commodified notions of the production, consumption, marketing, and

commercial exchange of organized sound(s) which largely define and

thereby (over)determine our present relationships to music in the

general political economy and culture.

Thus this magazine will

strive to critically question and go beyond the conventional imposed

notions and categories of what constitutes the generic and stylistic

definitions of 'Jazz', 'classical music', 'Blues', 'Rhythm and Blues',

'Rock 'n Roll', 'Pop', 'Funk', 'Hip Hop' etc. in order to search for

what individual artists and ensembles do creatively to challenge and

transform our ingrained ideas and attitudes of what music is and could

be.

So please join me in this ongoing visceral, investigative,

and cerebral quest to explore, enjoy, and pay homage to the endlessly

creative and uniquely magisterial dimensions of MUSIC in all of its

guises and expressive identities.

April 4, 2015--April 11, 2015

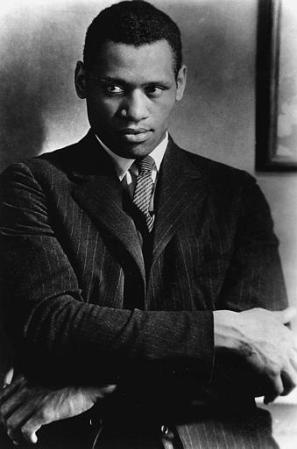

Billie Holiday (1915-1959): Legendary, iconic and innovative singer, songwriter, and ensemble leader

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER TWO

[In glorious tribute and gratitude to this great legendary artist we celebrate her centennial year]

FOR BILLIE HOLIDAY

by Kofi Natambu

by Kofi Natambu

Deep within her voice

there is a bird

and inside that bird is a song

and inside that song is a light

and inside that light is a Joy

and inside that Joy is a Monster

and inside that Monster is a memory

and inside that memory is a celebration

and inside that celebration is a hunger

and inside that hunger is a dance

and inside that dance is a moan

and inside that moan is a majesty

and inside that majesty is a longing

and inside that longing is a history

and inside that history is a mystery

and inside that mystery is a fear

and inside that fear is a truth

and inside that truth is a passion

and inside that passion is a whisper

and inside that whisper is a wolf

and inside that wolf is a howl

and inside that howl is a lover

and inside that lover is an escape

and inside that escape is a regret

and inside that regret is a fantasy

and inside that fantasy is a death

and inside that death is a life

and inside that life is a woman

and inside that woman is a scream

and inside that scream is a release

and inside that release is a power

and inside that power is a voice

and inside that voice is a song

and inside that song is a singer

and inside that singer is a Holiday

and inside that Holiday is Billie

there is a bird

and inside that bird is a song

and inside that song is a light

and inside that light is a Joy

and inside that Joy is a Monster

and inside that Monster is a memory

and inside that memory is a celebration

and inside that celebration is a hunger

and inside that hunger is a dance

and inside that dance is a moan

and inside that moan is a majesty

and inside that majesty is a longing

and inside that longing is a history

and inside that history is a mystery

and inside that mystery is a fear

and inside that fear is a truth

and inside that truth is a passion

and inside that passion is a whisper

and inside that whisper is a wolf

and inside that wolf is a howl

and inside that howl is a lover

and inside that lover is an escape

and inside that escape is a regret

and inside that regret is a fantasy

and inside that fantasy is a death

and inside that death is a life

and inside that life is a woman

and inside that woman is a scream

and inside that scream is a release

and inside that release is a power

and inside that power is a voice

and inside that voice is a song

and inside that song is a singer

and inside that singer is a Holiday

and inside that Holiday is Billie

Poem from the book THE MELODY NEVER STOPS by Kofi Natambu. Past Tents Press, 1991

THE DAY LADY DIED

by Frank O'Hara

by Frank O'Hara

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don't know the people who will feed me

I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun

and have a hamburger and a malted and buy

an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets

in Ghana are doing these days

I go on to the bank

and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)

doesn't even look up my balance for once in her life

and in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlaine

for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do

think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or

Brendan Behan's new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres

of Genet, but I don't, I stick with Verlaine

after practically going to sleep with quandariness

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfield Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face

on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don't know the people who will feed me

I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun

and have a hamburger and a malted and buy

an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets

in Ghana are doing these days

I go on to the bank

and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)

doesn't even look up my balance for once in her life

and in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlaine

for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do

think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or

Brendan Behan's new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres

of Genet, but I don't, I stick with Verlaine

after practically going to sleep with quandariness

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfield Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face

on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

This immortal poem about Billie written upon her death in 1959 is from

LUNCH POEMS by Frank O'Hara (City Lights, 1961)-- Pocket Poets Series

WKCR presents: The Billie Holiday Centennial Festival:

Tuesday, April 7th marks the 100th birthday anniversary of the one and

only Billie Holiday. We'll be celebrating the hauntingly honest, lyrical

virtuosity of Lady Day with a weeklong centennial broadcast, featuring

her entire 1933-1959 discography, as well as on-air interviews with

musicians and scholars. WKCR has a precedent of commemorating Holiday

and her incredibly important contributions to vocal jazz, jazz as a

whole, and Black music in our annual birthday broadcast schedule and in a

special 360-hour Billie Holiday Festival that aired in 2005.

Tune in to WCKR 89.9FM-NY or online at www.wkcr.org

from Sunday, April 5th at 2pm through Friday, April 9th at 9pm as we

spend a week listening to and examining the life, career, and

distinctive sound of Lady Day. We'll be posting a full broadcasting

schedule soon, but so far, look forward to a combination of continuous

and show-specific programming throughout the week.

April 3, 2015

The Art of Billie Holiday’s Life

By Richard Brody

The New Yorker

By Richard Brody

The New Yorker

Billie Holiday, like all great artists, is as distinctive, as idiosyncratic, as original off-stage and off-mike as on. Credit Photograph by Charles Hewitt / LIFE / Getty

Some biographies of artists take in the whole life—preferably with

equal attention to the work, and integrating the two elements to the

extent that the work invites it. Others offer a bio-slice or synecdoche,

centered on one particular period, relationship, or field of activity

to provide an exemplary angle on the life and work. John Szwed’s brief

but revelatory new book, “Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth”

(Viking), which comes out this week—just under the wire for her

centenary (Holiday was born April 7, 1915)—is in another category. It’s a

meta-biography, about the creation of Holiday’s public image in media

of all sorts: print, television, movies, and, of course, her recordings,

but with special attention to the composition of her autobiography,

“Lady Sings the Blues,” which was published in 1956.

Szwed, whose

other books include a superb biography of Sun Ra, “Space is the Place,”

reconstructs, through ardent archival research as well as his own

interviews, the circumstances of the making of Holiday’s book. In the

process, he both evaluates the first-hand significance of “Lady Sings

the Blues” as Holiday’s factual and emotional account of her own life—as

a record of Holiday’s experiences and ideas—and also, secondarily,

treats the writing and the publication of the book as important events

in Holiday’s life. She died on July 17, 1959, at the age of forty-four,

and had been suffering from liver disease and heart disease. She was, as

she writes, addicted to heroin “on and off” since the early

nineteen-forties. Szwed says that, when she went to the hospital in

1959, “No one at the hospital knew who she was, and with needle marks on

her body, she was left in the hall for hours, since the institution was

not allowed to treat drug addicts.”

Holiday’s recording career

was precocious: she made her first records in 1933, with a small group

headed by Benny Goodman (who wasn’t yet a big-band leader). On the very

first page of the first chapter, Szwed writes wisely about the timing of

Holiday’s own book, nothing that at the time it was published, “jazz

had moved from being the popular music of 1940s America to a more

rarefied place in the public view.” This fact, for Szwed, mitigated the

response that Holiday’s book received. The critics now defending jazz

were mainly “closet high modernists who wanted no mention of drugs,

whorehouses, or lynching brought into discussions of the music.” And

those are among the subjects addressed, in unsparing detail, in

Holiday’s book. (Among the critics who attacked the book was Whitney

Balliett, this magazine’s longtime jazz critic, who wrote about it in

the Saturday Review.)

The first section of Szwed’s book is one of

the most briskly revealing pieces of jazz biography that I’ve read.

First, he establishes the bona fides of William Dufty, Holiday’s

collaborator on the book, rescuing him from charges of being a hack.

Dufty was an award-winning journalist at the New York Post at a time

when it was a leading liberal paper; he and his wife, Maely Daniele, a

longtime friend of Holiday’s, welcomed her to their apartment as “a

place of refuge from the police, her husband Louis McKay, reporters, and

the various unsavory figures who haunted her life.” Dufty did the

actual writing, based on long and detailed conversations with Holiday

augmented by archival research that sparked her recollections.

Szwed sketches a handful of the book’s divergences from the

independently established biographical record, starting with the

legendary first sentences: “Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when

they got married. He was eighteen, she was seventeen, and I was three.”

Szwed explains, “When Billie was born, her mother was nineteen, her

father seventeen. They never married . . . She was born not in Baltimore

but in Philadelphia. Some questioned her claim of having been raped at

age ten.”

Holiday’s book is unstinting in its depiction of the

hardships she faced. As a child, she heard from her great-grandmother

about life as a slave; she grew up away from her mother, in the home of a

cousin who beat her; she scrubbed floors in a “whorehouse” in order to

hear music on the record player; and the man who raped her when she was

ten was a neighbor. She quit school at twelve and travelled to New York

alone, where she worked first as a maid and then as a prostitute. Jailed

and released, she moved in with her mother, who lived in Harlem. They

were on the verge of eviction when Holiday, who was about fifteen, got a

job singing—more or less by accident—at a local nightspot. Holiday

details the roughness of the world of music, exacerbated by relentless

racism—travelling through the South in the age of Jim Crow, being forced

to darken her skin with makeup in order to perform in Detroit. She

describes in detail her addiction to heroin, her resulting troubles with

the law, and its impact on her career.

For all its confessional

frankness and accusatory clarity, there is, as Szwed reveals, much more

to her story—and the circumstances of the composition of “Lady Sings the

Blues” are an exemplary part of it.

Delving into earlier drafts

of “Lady Sings the Blues” and other archival materials, Szwed finds

echoes of the book in other published sources to which Holiday had

referred Dufty as particularly reliable. Holiday told Dufty some stories

that were ultimately kept out of the book, including the agonizing home

abortion that her mother forced her to undergo as a teen. But Szwed

finds that the book’s most important omissions were demanded by lawyers

(including one representing Holiday and McKay) and by many of the public

figures who played major roles in Holiday’s life and autobiography.

In particular, Szwed traces the stories of two important relationships

that are missing from the book—with Charles Laughton, in the

nineteen-thirties, and with Tallulah Bankhead, in the late

nineteen-forties—and of one relationship that’s sharply diminished in

the book, her affair with Orson Welles around the time of “Citizen

Kane.”

In 1941, Welles wanted to make a film called “The Story of Jazz,” in collaboration with Duke Ellington. It would be set in the nineteen-teens and twenties, centered on the rise of Louis Armstrong, playing himself. He wanted Holiday to play Bessie Smith. Welles’s movie, Szwed writes, was “intended to be radically innovative, mixing together different styles of jazz, using the surrealist drawings of Oskar Fischinger.” It was put off, Szwed reports, due to the start of the Second World War. When Welles went to Rio to make “It’s All True,” he thought that the jazz story could be woven into it—but his filming of “the everyday interaction of races in Brazil” soured Welles’s studio, RKO, on the entire production.

The basic idea is the crucial one:

of all jazz singers, Holiday is the one who is a jazz musician, the

equal in musical invention of the epoch-making instrumentalists who

played alongside her. Szwed picks up on the negative effect on her

career that her style risked when she was starting out. He quotes one

club manager who told her, “You sing too slow . . . sounds like you’re

asleep!” Music publishers—who still made lots of money from the sale of

sheet music—didn’t like her singing, which didn’t present the melodies

clearly enough. His analysis shines all the more brightly when he goes

behind the scenes of the recordings to unfold the life of

performance—her initial experience as a cabaret singer, going table to

table for tips in the Prohibition-era cabarets on 133rd Street, where

she got her start; the peculiarities of the Fifty-Second Street clubs

where she performed in the late thirties, which fostered a casual

musical intimacy (“They were small, maybe fifteen feet by sixty feet,

and were located in the basements of brownstone residences. They

featured miniature tables for a few dozen people.”). He also explains

the painful conditions of some of her later recordings, when her health

and her voice were in bad shape (“The on-the-spot rehearsals, the false

starts, retakes, and overdubs began to pile up on the tape reels”).

Szwed looks closely at her choice of songs and the origins of ones with

which she’s closely associated, including “Strange Fruit” and “God

Bless the Child.” He details the life-threatening conflicts that she

faced on the road in the South, where she performed as a member of the

(white) Artie Shaw band. And he carefully considers the specifics of

performance later in her career, when she sang at Carnegie Hall and

recorded with far more elaborate arrangements than she had used in her

youth—and focusses on the musical implications of these circumstances.

Above all, in analyzing her art, Szwed argues for the difference

between the performer and the life—between the on-stage persona and the

person: “Her ability to communicate strong and painful emotions through

singing led many to believe that she was suffering and in real pain. But

real suffering is not necessary for great singing, only the ability to

communicate it in song . . . Like actors, singers create their

identities as artists through words and music. . . . All we can know for

certain is the performance itself.”

In general, the desire of

even the most discerning critics, such as Szwed, to separate art and

life, to analyze the formal traits of works as if they were dissociable

from the experience and the emotions that inspire them and that they

convey, is both noble and doomed—noble, because artists deserve to be

honored for their achievements, and doomed, because the formal and

systematic nature of those achievements isn’t what makes them endure.

The individuality, the immense complexity of inner life that art

conveys—including Holiday’s seemingly straightforward and instantly

appreciable art—doesn’t occur in a laboratory-like isolation.

Holiday herself, in “Lady Sings the Blues,” took care to depict the

unity of her personal life and her musicianship, starting with the

haphazard circumstances under which she began her career, as a teen-age

ex-prostitute in need of a fast way of making rent for herself and her

mother. She specifically connects the way she sings with her

experiences—and with her readiness to face them. (“Maybe I’m proud

enough to want to remember Baltimore and Welfare Island.”)

Holiday, like all great artists, is as distinctive, as idiosyncratic, as

original off-stage and off-mike as on. The life doesn’t explain the

art; rather, life is an art in itself—whether a creation of sublime

moments and fascinating gestures, or of terrifying confrontations and

mighty endurances—that is illuminated by the same inner light, inspired

by the same genius, inflected by the same touch that makes the works of

art endure on their own. The biographer of an artist is a critic in

advance, in acknowledging and appreciating the actions of an artist’s

life and recognizing what’s personal and distinctive in their being—in

discerning the artistic aspect of the life. Szwed, in his brief book,

accomplishes this goal, perhaps even better than he intended.

Richard Brody began writing for The New Yorker in 1999, and has

contributed articles about the directors François Truffaut, Jean-Luc

Godard, and Samuel Fuller. He writes about movies in his blog for newyorker.com.

Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth review – reclaiming Lady Day's artistry

Everyone knows about the sex and drugs – but John Szwed’s biography

makes the case for Holiday as a complex artist who inspired in many

different directions

Billie Holiday: one of the most famously

indescribable – and inimitable – voices in all of jazz and pop-music

history. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives

by Seth Colter Walls

Thursday 2 April 2015

The Guardian (UK)

Thursday 2 April 2015

The Guardian (UK)

To the public, Billie Holiday might simply be an icon. But to

specialists, she’s the subject of a long and unsettled argument. In the

view of some critics, her art has often gotten short shrift compared

with discussions over the tabloid particulars of her too-short life. In

1956, she published a co-written autobiography called Lady Sings the

Blues, which tried to balance confessional storytelling with assertions

of her artistic control. It was accused of doing a disservice to jazz by

some self-appointed guardians of the genre.

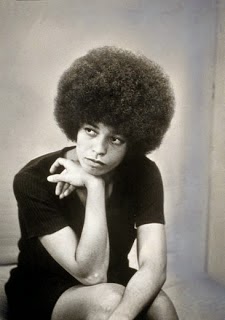

In later decades,

Lady Day – as she was called by fans and fellow musicians – was even

accused of having been illiterate. A fast-and-loose 1972 biopic starring

Diana Ross, a pop singer ill-suited to capturing Holiday’s swinging

sophistication and melodic genius, hardly improved anyone’s

understanding. The feminist critic Angela Davis took sharp exception to

the film, writing that it “tends to imply that her music is no more than

an unconscious and passive product of the contingencies of her life”.

With the approach of Holiday’s centenary, more and more people are

coming over to Davis’s side. John Szwed’s swift, conversational and yet

detail-rich new biography, Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth,

communicates its artist-first priorities in the subtitle, and then makes

good on them throughout. That’s not to say that he ignores the singer’s

romantic flings (with Orson Welles, among others), the domestic abuse

suffered at the hands of multiple partners or the long-term heroin use

that are part of the familiar Holiday lore. Crucially, though, he spends

more than half his page-count closely considering Holiday’s music. And

his book comes just as three new recordings – one from José James, a

singer who skillfully bridges the worlds of contemporary R&B and

jazz, one by Cassandra Wilson and another by the classical pianist Lara

Downes – likewise investigate the musician’s catalogue with respectfully

daring air.

As tough as it is for those musicians to interpret

songs Holiday made iconic, it’s possible that Szwed’s challenge was more

daunting. He is writing in the wake of Holiday biographies that have,

by necessity, relied on speculation and hearsay, given the fact that

Holiday gave few interviews (and saw her autobiography redacted by a

lawsuit-averse publisher). There are also political ambiguities involved

in narrating the choices of an African American artist who, as Davis

noted, “worked primarily with the idiom of white popular song”. And then

there are the difficulties of needing to describe one of the most

famously indescribable – and inimitable – voices in all of jazz and

pop-music history.

On the latter point, Szwed clears his throat a

bit – quoting divergent critical opinions and eminent musicologists –

displaying some of the agonies that prose suffers when summing up the

Holiday sound. But he does have moments where he succeeds beautifully:

“In the upper register she had a bright but nasal sound; she sounded

clearer, perhaps even younger, in the middle; and at the bottom, there

was a rougher voice, sometimes a rasp or a growl. But even these voices

were varied or might change depending on the song she was singing.”

Elsewhere, Szwed is on point when he describes Holiday “falling behind

the beat, floating, breathing where it’s not expected, scooping up notes

and then letting them fall”.

As the author of compelling books

on complex figures such as Miles Davis and Sun Ra, it’s little surprise

that Szwed is also wise and authoritative on the sad, complex

interaction of Jim Crow racism and early pop-music practices, in the

20-page chapter The Prehistory of a Singer. And he proves as good at

reading Holiday’s political choices – such as revising the “in dialect”

lyrics of Gershwin’s I Loves You, Porgy – as he is at spelling out

Holiday’s evolving approach to improvisation, over the course of her

career.

Like Davis, Szwed hears a hint of feminist

consciousness-raising in Holiday’s 1948 rendition of My Man. And on the

tortured history of credit-taking for the composition of Strange Fruit –

the anti-lynching protest song that stunned one nightclub audience

after another, once Holiday added it to her repertoire – Szwed cuts

through the brush to show the ways in which Holiday’s melodic approach

(as well as her choice to perform it in front of white people) destined

the song for a place in history as much as anything else.

If it

sounds like the accumulated weight of history makes for solemn reading, a

lot of fun can actually be had using Szwed as a listening partner. Go

ahead and launch your streaming-music engine of choice and build a

playlist with the tracks as Szwed considers them. You probably won’t

need much help enjoying three rare Holiday recordings with Count Basie’s

1937 band – available on disc eight of Lady Day: The Complete Billie

Holiday on Columbia, 1933-1944 – since the musicians’ collective brand

of ecstasy requires little in the way of selling. But Szwed’s

description of Holiday “gliding over rhythm suspensions and finding her

way over the glassine 4/4 of a great swing rhythm section” is a treat –

as is his song-by-song investigation of Holiday’s musical partnerships

with the pianist Teddy Wilson and the saxophonist Lester Young.

In the case of pre-existing songs that Holiday made her own, Szwed cites

earlier recordings by other singers before inviting you to compare them

with what he deems to be Holiday’s best version (the better to put her

skills in relief). And when it comes to the core of Lady Day’s catalogue

– the songs she recorded, with great variance, during multiple phases

of her career – Szwed’s listening notes shed useful light on the

differences, especially for fans who think they can safely dismiss the

portion of Holiday’s discography that is less favoured by jazz

aficionados.

That very hybridity – Holiday’s ability to help

define jazz singing, and then buck the genre’s conventions – is what

makes the new spate of tributes to her feel so appropriate. A listener

might disagree with an arrangement choice made by Cassandra Wilson, on

Coming Forth By Day, or else miss elements of swing in Lara Downes’s

classical recital A Billie Holiday Songbook – but their risk-taking is

clearly in the service of honoring Holiday’s often-surprising moves.

(José James’s Yesterday I Had the Blues: The Music of Billie Holiday is

just about perfect, including as it does the playing of

MacArthur-winning pianist Jason Moran.)

Plenty of stars from

yesteryear had crazy-juicy personal lives; very few left behind

conceptual approaches that inspire in so many directions. Each of these

new albums is in league with Szwed’s book – a joint persuasion campaign

meant to encourage us to consider musicianship as the defining

characteristic of Lady Day’s legacy. That’s about as fine a

centenary-year gift as anyone had a right to expect.

Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth is published by Viking Press in the USA, and William Heinemann in the UK

When Billie played her yearly concerts at the Apollo and at Carnegie

Hall everyone came out in full force either to hear her sing or to see

whether she was still together. Each time a new record was issued it was

compared with her early ones, and she was often judged to be imitating

herself, to be working with the wrong musicians, the wrong arrangers,

etc. Most everyone liked to believe that Billie made her best records

when she sang with Count Basie and the other geniuses of swing. It's

hard to disagree, for she was, like all of them, an incredible horn in

those days. Billie's later records, usually in a much slower tempo, are a

different music. They are the songs of a woman alone and lonely and

without much sympathy. No one blows pretty solos behind her like Lester

did. Sometimes there are unintelligent voices in the background going

oo-oo-oo with none of the wit Billie had on "Ooo-oo-oo what a lil

moonlight can doo-oo-oo." Nevertheless, these are the songs of Lady Day

too, and if the sorrow sounds a little heavier it was because she'd been

carrying it a while. "I remember when she was happy-" Carmen McRae said

in 1955, "that was a long time ago."

Billie and Louis both were

arrested in 1956. Billie knew by this time that if the Narcotics Bureau

wanted to get her it only had to be arranged, the evidence "found" and

she could be convicted on her past record. In her book she pleaded that

the addict be treated rather than punished. She knew how little good

punishment had ever done to help her. And her stated purpose in

revealing all that she considered shameful in her life was to warn young

people away from heroin. "If you think dope is for kicks and for

thrills, you're out of your mind.... The only thing that can happen to

you is sooner or later you'll get busted, and once that happens, you'll

never live it down. Just look at me."

Billie never was able to

stop using heroin completely, though she tried very hard. Some people

thought she could have tried harder: "That girl's life... was just

snapped away from foolishness." But there were others who knew and loved

her. Lena Horne and Billie had been friends since Cafe Society days,

and she understood how life had been spoiled for Billie.

Billie

didn't lecture me - she didn't have to. Her whole life, the way she

sang, made everything very plain. It was as if she were a living picture

there for me to see something I had not seen clearly before.

Her

life was so tragic and so corrupted by other people-by white people and

by her own people. There was no place for her to go, except finally,

into that little private world of dope. She was just too sensitive to

survive.

Billie survived long enough to sing a few days at the

Five Spot, a club that opened in downtown New York in the fifties. Her

last appearance was at the Phoenix Theater in New York in May, 1959. On

May 31 she was brought to a hospital unconscious, suffering from liver

and heart ailments, the papers said. Twelve days later someone allegedly

found heroin in her room. She was arrested while in her hospital bed

and police came to guard her, to make sure this now thin, suffering

woman could not get away from the law one more time. But she escaped the

judgment of the United States of America versus Billie Holiday for a

higher judgment, on July 17, 1959.

Billie Holiday at 100: Artists reflect on jazz singer’s legacy

By Aidin Vaziri

Friday, April 3, 2015

Photo: Associated Press

Image 1 of 13

FILE - This Sept. 1958 file photo shows Billie Holiday. The Apollo

Theater is planning events to commemorate the 100th birthday of Holiday.

The legendary American jazz vocalist was born on April 17, 1915 and

died in 1959 at the age of 44. Holiday performed at least two dozen

times at the Apollo. She will be inducted into its Walk of Fame on April

16, 2015. (AP Photo/FILE)

Billie Holiday would have turned 100

this week, but who’s counting? The famed jazz singer and songwriter’s

voice is ageless, still luring fans with its effortless swagger and

unblinking candor. It carried with it all the difficulty she endured

throughout her tumultuous life — born Eleanora Fagan, an illegitimate

child, on April 7, 1915, in Baltimore; died strung out and broken 44

years later in New York — along with all the hope, fear and desperation

that came with it. “What comes out is what I feel,” she once said.

No one else can sound like Billie Holiday because no one else lived like Billie Holiday.

Yet in generation after generation, her influence is unmistakable. To

mark the centennial of her birth, which will be celebrated with

concerts, books, albums, tributes and reissue packages around the world,

we spoke with some people closer to home whose lives were deeply

touched by Holiday.

Paula West

Longtime Bay Area jazz singer, torchbearer of the American Songbook popularized by Holiday

I’m not quite sure when I first heard Billie Holiday. I believe it was

before the Diana Ross biopic (“Lady Sings the Blues”) was released. Of

course their voices were dissimilar. I was young at the time, and had

only been exposed to those “greatest hits,” such as “Fine and Mellow,”

“Them There Eyes” and “Good Morning Heartache.”

I feel the best

singers have always been able to get across the raw emotions of the

lyrics. She had no great vocal range, but that was never needed. It was

about telling the truth, the story, and not too many singers could ever

match her natural interpretations. No vocal histrionics, melisma

necessary. She was respected by musicians, as well, and her singing was

influenced by musicians such as Louis Armstrong.

There are dozens

of her interpretations I love, but “Lady in Satin” is my favorite,

particularly her version of “I’m a Fool to Want You.” The arrangement is

beautiful yet heartbreaking, of course, and no one could deliver that

better than Billie Holiday.

Lavay Smith

Blues and jazz singer with Lavay Smith & Her Red Hot Skillet Lickers, renowned for her tributes to the first ladies of jazz

I remember seeing Billie Holiday singing on TV on an oldies station

that would show the Little Rascals, Shirley Temple and old

black-and-white movies. Like everyone who hears her, I loved her right

away.

Billie remains an icon because she was true to herself. As a

singer, she made you believe that she meant every word she sang. Lyrics

were very important to her, which isn’t true of all jazz singers. And

the feeling that she creates through her use of rhythm was always

swingin’ and happy. A lot of people think of her music as being sad, but

she had a great sense of humor that comes through, and I’ve always

found her music to be uplifting.

The first album I bought was

“Lady Sings the Blues,” and I played the heck out of. It included

“Strange Fruit” and many of her hits, like “Traveling Light” and “Good

Morning Heartache.” I love all of the Columbia recordings that she did

with Lester Young and Teddy Wilson, including all of the obscure songs. I

just love the feeling and the soul of these records. The interplay

between Billie and Lester Young is the textbook definition of how an

instrumentalist should interact with a singer.

Joey Arias

New York cabaret singer and drag artist, who recently performed a tribute to Billie Holiday at Lincoln Center

New York cabaret singer and drag artist, who recently performed a tribute to Billie Holiday at Lincoln Center

I remember hearing her voice and thinking how lovely she sounded. I

wanted to have that same sound that she was emoting. It was a magic

spell that was sent to me. I feel as though we were connected at the hip

from stories I’ve heard from friends and family.

Billie was an

outspoken person. She was class all the way and never wanted to be

treated any other way. She was being followed and became public enemy

for standing up for her rights and acting strong and never letting her

guard down. She dressed beautifully and had such presence.

“Lady in

Satin” is my favorite album. It all depends on what period you want to

hear her style, but I love her in the late ’50s. She summed it all up —

her life, her singing and her thoughts, and her love of life and love.

Randall Kline

SFJazz executive director

SFJazz executive director

I heard her on the home stereo as a teenager. My parents were jazz

fans. One hearing of her voice — soft, persuasive, mournful, honest,

beautiful — told you to listen more closely. “Don’t Explain” for its raw

pathos. “Strange Fruit” for its power, poignancy and, sadly, its

contemporary relevance.

Getting to know Billie Holiday

Here are some albums to help you get better acquainted with the jazz singer’s magic.

“Lady Day: The Best of Billie Holiday,” Legacy. A two-CD set containing

many of the classic sides Holiday cut for Columbia and its Brunswick,

Vocalion and Okeh labels in the 1930s and early ’40s, including “What a

Little Moonlight Can Do,” “A Fine Romance,” “You Go to My Head” and “The

Man I Love.”

“Billie Holiday: The Complete Decca Recordings,”

GRP. An excellent two-CD box featuring the torch songs, raucous

renditions of signature Bessie Smith numbers, and other material Holiday

recorded for Decca from 1944 to 1950.

“Lady in Autumn: The Best

of the Verve Years,” Verve. A good two-disc survey of Holiday’s

small-band recordings of the 1950s, featuring stellar soloists like Ben

Webster and Benny Carter.

“Lady in Satin,” Legacy. A

heartbreaking beauty. Writer Michael Brooks wrote that this 1958 album

feels “as if a group of family and friends are gathered around a loved

one and saying their last goodbyes.”

“Ken Burns Jazz — Definitive

Billie Holiday,” Verve. Compiled by the documentary filmmaker, this

single-disc collection culls material from the three major phases of the

singer’s career. — Jesse Hamlin

Kitty Margolis

San Francisco jazz singer, trustee at the Recording Academy, founder of Mad-Kat Records

I remember staring at a girlish, chubby Billie on the cover of this

brown Columbia three-LP box set released in 1962, “Billie Holiday: The

Golden Years.” It had an extensive photo book with detailed track

listings inside and liner notes by John Hammond and Ralph Gleason. I

still have it. Opening it and smelling the paper takes me right back. I

realize now that a lot of the tunes in this box became very important to

my early core repertoire.

I don’t think there is one genuine female jazz singer in the world who doesn’t have Billie inside. She defined the idiom.

One major thing that set Billie apart as a jazz singer is that she was a musician’s singer, a master improviser without ever uttering one scat syllable. She was not a classically “pretty”-sounding singer like Ella or Sarah. Billie’s sound was a bittersweet brew: raw, tart, personal, intimate, relaxed, understated, urgent.

Billie’s storytelling was always 100 percent emotionally

intelligent and believable, an ironic cocktail of longing, pride, pain,

strength with a sharp glint of humor. No one could sound happier (“Them

There Eyes”) and no one could sound darker (“I’m a Fool to Want You”).

Billie sang the truth. There was no “acting” involved. She could take

even the most banal pop lyric of the time and imbue it with subtext that

gave it a much deeper message, almost like a code.