A Critical Review of a "Review":

The White Supremacist Incompetence of New York Times "literary critic" Dwight Garner vs. the literary and cultural WORK and achievements of Amiri Baraka from 1961-2013

The White Supremacist Incompetence of New York Times "literary critic" Dwight Garner vs. the literary and cultural WORK and achievements of Amiri Baraka from 1961-2013

by Kofi Natambu

The Panopticon Review

The Panopticon Review

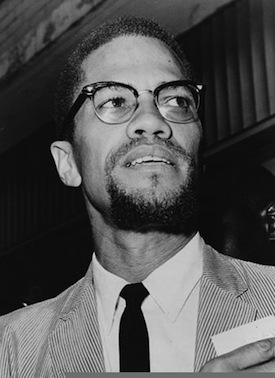

DWIGHT GARNER

(b. 1965)

NEW YORK TIMES LITERARY CRITIC

“We know that the war against intelligence is always waged in the name of common sense.”

― Roland Barthes, Mythologies

As U.S. History—social, cultural, economic, and political—notoriously and repeatedly reveals to us, the sustained relentless brutality and perversely willful ignorance and self serving arrogance of White Supremacy (forever masked in this country by the always handy and rhetorically vague euphemism called “racism") is simultaneously conscious, subconscious, and unconscious behavior no matter who is engaging in it. Moreover, in the living ideological and empirical context of a society and culture eyebrow deep in the vast and thoroughly rancid ocean of lies, distortions, aporias, evasions and denials intrinsic to the white supremacist intellectual mindset (and practice), the knee-jerk default position that one takes is nearly always one of an insistently dismissive and rank condescension toward the black subject/object/target of one’s middlebrow contempt and patronizing indifference. Thus instead of an intelligently considered and even minimally rational and focused critical analysis of the actual range and scope of the black object’s actual work and contributions we inevitably are subjected instead to an outrageously myopic reductionism and lazy simpleminded a priori rejection of the work in favor of a smugly self satisfied and mindless incompetence buttressed by an utterly defensive witlessness masquerading as “insight.” The result is the idiotic pseudo psychoanalytic bile and corny extraliterary judgment and moral posturing that Mr. Garner has conjured here instead of a mature, even minimally competent critical review of the actual “gift and achievements” of Amiri Baraka’s WORK over a half century. For example as Garner conveniently refuses to even acknowledge, let alone responsibly engage, regardless of what anyone thinks otherwise nearly every major writer or artist in history worth even a modicum of our attention and regard is necessarily and by definition a raft of internal and external contradictions and unresolved tensions that one may like or dislike, understand or are clueless about, identify with or disdain. But what pray tell does any of that have to do with the actual “gift and achievements” of their work? Far more relevant here is what does any of that has to do with a genuine critical assessment and engagement of this work? T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound (just to name two of the endless number of famously white “mainstream" canonical examples one could cite) were both notoriously racist, sexist, and fascist minded snobs steeped in religious bigotry and secular hatreds whose highly contentious relationship to a wide array of people and cultures deeply rankles, upsets, offends, and horrifies many to this day (and largely for very good and substantive reasons) but in the FINAL ANALYSIS what does that have to do with determining whether or not Pound and Eliot were great poets and critics whose actual “gifts and achievements” were still extremely important and of immense artistic and intellectual value creatively to the theory and practice of poetry and literary expression whether one “liked” or “identified” with them or not.

In the case of Amiri Baraka my point is that even if Garner foolishly but honestly thought Baraka’s work overall was somehow unworthy of his or our collective attention he would still have to make the intellectual and analytical EFFORT at minimum to seriously and critically investigate and thus intelligently ascertain exactly what he thought Baraka’s work did and didn’t do in his literary career in order to share his opinions and ideas about the relative value (or lack thereof) of Baraka’s work for his criticism to have any kind of useful validity. But Garner does not come anywhere close to that basic level or standard of competency as a literary critic or even disinterested academic observer of Baraka’s fifty year oeurve. The reasons Garner utterly fails to do that is because he’s such a willfully smug, arrogant, condescending, and absurdly patronizing literary policeman who simply pretends he always already “knows” who and what Baraka is and isn’t as a writer and cultural force that he clearly thought/felt it was beneath his station or position (status?) to do what is REQUIRED of him toas a critic. In its place we get instead some silly infantile bullshit about Baraka’s “personality" (or what is absurdly construed by Garner to be Baraka’s personal psychology). Talk about rhetorical dishwater. It sounds to me like Garner has been drinking it! By dismissively reducing Baraka’s poetry to being “full of tantrums and sophistries” and Baraka himself to a mere “malcontent” who wore his “id on his sleeve” and was “ tightly wound” and who “wanted to slice up "the white man" (could Garner possibly mean himself?) like a spiral ham” what we decidedly don’t get is a real literary critic capable of explicating and expressing ideas and opinions worth reading and (gasp!) actually thinking seriously about one way or the other. Instead we get the pompous adolescent blurtings of a junior/bush league pop psychologist. Anything else that Baraka has to offer as a major poet and intellectual Garner assures us without a hint of evidentiary information or analysis is nothing but “many, many deficiencies of coherence” that Garner couldn’t or didn’t want to grasp because it’s relatively unimportant or meaningless to him. Further as Baraka embraced a series of differing ideological positions we are told by Garner the presumptuous self proclaimed sage that Baraka's “political voice ran over his poetic one” (a falsely dichotomous theoretical split of political ideology and poetics if there ever was one) and that process in turn introduced some truly bad and contemptible things to emerge in his poetry. What an insufferable intellectual fraud! As Roland Barthes pointed out so eloquently in his early literary and critical theory opus Mythologies (1956) Garner is the very embodiment of that creepy species of narcissistic sophistry known as “blind and dumb criticism.” By way of a concluding sortie on this rampant tendency by far too many white American “critics” like Mr. Garner to blithely and unjustly condescend to, marginalize, and patronize various literary personas and “public personalities" rather than genuinely analyze and critique their actual literary production and output --and especially as it is pervasively and rather routinely applied to black writers in the United State--Barthes strikingly prescient views are still quite germane:

"Why do critics thus periodically proclaim their helplessness or their lack of understanding? It is certainly not out of modesty: no one is more at ease than one critic confessing that he understands nothing about existentialism; no one more ironic and therefore more self-assured than another admitting shamefacedly that he does not have the luck to have been initiated into the philosophy of the Extraordinary; and no one more soldier-like than a third pleading for poetic ineffability. All this means in fact that one believes oneself to have such sureness of intelligence that acknowledging an inability to understand calls in question the clarity of the author and not that of one's own mind. One mimics silliness in order to make the public protest in one's favour, and thus carry it along advantageously from complicity in helplessness to complicity in intelligence. It is an operation well known to salons like Madame Verdurin's: 'I whose profession it is to be intelligent, understand nothing about it; now you wouldn't understand anything about it either; therefore, it can only be that you are as intelligent as I am…"

"...In fact, any reservation about culture means a terrorist position. To be a critic by profession and to proclaim that one understands nothing about existentialism or Marxism (for as it happens, it is these two philosophies particularly that one confesses to be unable to understand) is to elevate one’s blindness or dumbness to a universal rule of perception, and to reject from the world Marxism and existentialism: 'I don’t understand, therefore you are idiots.’ But if one fears or despises so much the philosophical foundations of a book, and if one demands so insistently the right to understand nothing about them and to say nothing on the subject, why become a critic? To understand, to enlighten, that is your profession, isn’t it? You can of course judge philosophy according to common sense; the trouble is that while 'common sense' and ‘feeling' understand nothing about philosophy, philosophy, on the other hand, understands them perfectly. You don't explain philosophers,but they explain you. You don't want to understand the play by Lefebvre the Marxist, but you can be sure that Lefebvre the Marxist understands your incomprehension perfectly well, and above all (for I believe you to be more wily than lacking in culture) the delightfully 'harmless' confession you make of it.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/28/books/s-o-s-poems-1961-2013-works-by-amiri-baraka.html?ref=topics&_r=0

Books

Poetic Voice Wrapped Tight in Its Shifting Politics

S O S: Poems 1961-2013

By Amiri Baraka

531 pages. Grove Press. February, 2015. $30.

JANUARY 27, 2015

Books of The Times

By DWIGHT GARNER

New York Times

There are two ways to rank writers, the poet John Berryman said, “in terms of gift and in terms of achievement.”

Amiri Baraka (1934-2014) had a bold gift. His best poems are cynical, impolite, acid in their wit’s rain. He tapped easily into the suspicion and resentment that linger below the promise of American life. He was the keeper of a certain vinegary portion of the African-American imagination. He declared, over and over, that he would not be fooled again.

You can open to nearly anywhere in the first third of “S O S: Poems 1961-2013,” a career-spanning new collection of his work, and find fresh evidence of his capacities. In a poem called “Three Modes of History and Culture,” from 1969, a kind of updated Muddy Waters blues, he caught the faces of those in “trains/leaning north, catching hellfire in windows, passing through/the first ignoble cities of missouri, to illinois, and the panting/Chicago.”

What’s best about Baraka’s verse is that this historical sensibility and sense of historical dread bump elbows with anarchic comedy. “I have slept with almost every mediocre colored woman/on 23rd St,” he declares in a poem from “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note” (1961), his first collection of verse. In another poem from that collection, he asks:

What can I say?

It is better to have loved and lost

Than to put linoleum in your living room?

You were never sure what Baraka was going to say next, and for a writer, that’s not an insignificant gift to possess.

Baraka’s achievements, “S O S” makes plain, were only rarely equal to his talents. He went from beatnik to black nationalist to Marxist, and his political voice slowly ran over his poetic one, his dogma over his karma, to reverse the joke. Misogyny and anti-Semitism began to filter into his work.

In The Village Voice in 1980, he published an essay called “Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite.” But a poem titled “Somebody Blew Up America,” written shortly after Sept. 11, contains these lines:

Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed

Who told 4,000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers

To stay home that day

Why did Sharon stay away?

The funny thing about “Somebody Blew Up America” is that much of the rest of it is terrifically clarifying in its anger. It’s a vernacular poem, meant for the ear perhaps more than the eye, and it asks the oldest and juiciest questions about inequality:

Who own them buildings

Who got the money

Who think you funny

Who locked you up

Who own the papers

Who owned the slave ship

Who run the army

Who the fake president

Who the ruler

Who the banker

Who? Who? Who?

Now there’s a pop quiz for every sentient soul. Here is your blue book. You have 15 seconds.

“S O S” is the best overall selection we have thus far of Baraka’s work, but he is served poorly by it. The introduction by Paul Vangelisti, the volume’s editor, is an anthology of unforced errors.

Mr. Vangelisti neglects to provide the most basic details of Baraka’s life, so these poems are shorn of context. He also writes academic jargon of the sort Baraka despised, referring to one poem as “driven by the nuances of shifting, heterogeneous cadences, often spoken, often collaged, and always relentlessly material and public.”

This is the kind of rhetorical dishwater that can just as easily apply to a Meghan Trainor song or a Fox News segment.

Mr. Vangelisti provides only the vaguest sense of how the poems in this volume were selected and misses a crucial opportunity to set the entirety of Baraka’s oeuvre in necessary context. What were the criteria? What exactly was left out? We do learn that “S O S” comprises the contents of two earlier selections of Baraka’s work, selections the poet oversaw.

You would not know from this introduction, for example, that one of the poems Baraka left out included this line: “I got the extermination blues, jewboy.” The poems in the last section of “S O S” were selected by Mr. Vangelisti after the poet’s death.

Baraka knew he was wound tight. “I am a mean hungry sorehead,” he writes. “Do I have the capacity for grace??” He long had the sense he’d been “undesirably discharged/From America.” His internal struggles — he wore his id on his sleeve — are rarely less than interesting. “I wanted to know myself,” he writes, “and found this was a lifetime’s work.”

The pleasures in “S O S” tend to be mean or pointed, and funny and very real. He asks in one short poem,

If Elvis Presley/is

King

Who is James Brown,

God?

Another reads in its entirety,

How amazed the crazed

negro looked informed

that Animal Rights had

a bigger budget

than the N.A.A.C.P.!

He had little time for organized religion. A poem from 1972 begins,

We’ll worship Jesus

When jesus do

Somethin

When jesus blow up

the white house

or blast Nixon down

when jesus turn out congress

or bust general motors to

yard bird motors.

Baraka’s poems are filled with tantrums and sophistries, stances and dances. There are many, many deficiencies of coherence. Some make only the dead, clicking sound cars make in the frost. But others plant a hatchet in your skull that you won’t be able to pull out for weeks. Especially the ones in which he seems to want to slice up the white man like a spiral ham.

Baraka, who can almost be viewed as an intense and wary reverse image of Whitman, was a malcontent who contained multitudes. “Get your pitch forks ready,” he writes in a late poem collected here. “Strike Hard and True. You get them or they get you.”

S O S

Poems 1961-2013

By Amiri Baraka

531 pages. Grove Press. $30.

Dwight Garner (critic)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Born January 8, 1965 (age 50)

Fairmont, West Virginia, United States

Occupation Writer, journalist

Genre Criticism, nonfiction

Dwight Garner (born 1965) is an American journalist, now a literary critic for The New York Times. Prior to that he was senior editor at the New York Times Book Review, where he worked from 1999 to 2009. He was also the founding books editor of Salon.com,[1] where he worked from 1995 to 1998.

His essays and journalism have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harper's Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, the Oxford American, Slate, the Village Voice, the Boston Phoenix, The Nation,[1] and elsewhere. He has served on the board of the National Book Critic's Circle. In a January 2011 column for Slate, the journalist Timothy Noah called Garner a "highly gifted critic" who had reinvigorated the New York Times's literary coverage, and likened him to Anatole Broyard and John Leonard.[2]

He is the author of Read Me: A Century of Classic American Book Advertisements, and he is at work on a biography of James Agee.

Dwight Garner was born in West Virginia[3] and graduated from Middlebury College.[4] He lives in Frenchtown, New Jersey. He is married to the cookbook writer Cree LeFavour.[5]

http://heatstrings.blogspot.com/2015/02/save-our-stanzas-selecting-amiri-baraka.html

Saturday, February 07, 2015

Save Our Stanzas - Selecting Amiri Baraka

by Aldon Lynn Nielsen

Heartstrings

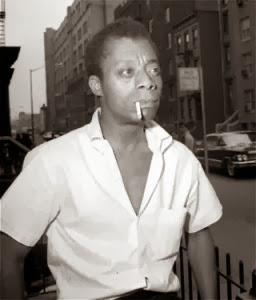

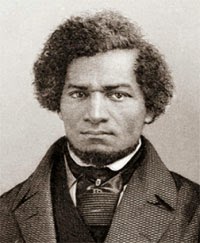

AMIRI BARAKA

(1934-2014)

For many years I have complained loudly and often about the lack of a readily available major gathering of Amiri Baraka's poetry. It would be hard to think of another late career poet of his importance who was not the subject of a Collected as well as a Selected. (The Complete generally awaits the poet's demise -- but even then . . .. Recollect that one of Frank O'Hara's friends asked, following the publication of both the Collected and Poems Retrieved, whether a Complete was even a possible thing. Looking at the masses of Baraka's work, I have often wondered the same thing.)

Long out of print, the Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, published in 1979, was advertised as "containing those poems which the author most wants to preserve," and that has long been the most substantial collection of Baraka's verse we had - 339 pages running from Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note through to Poetry for the Advanced. (This was the only volume in which many of us could find that second collection from Baraka's Marxist epoch.) There was no editor named in the book, so one assumes the selections are indeed Baraka's own.

A quarter century on, Marsilio published Transbluesency: Selected Poems 1961-1995, edited by Paul Vangelisti in consultation with the poet. I loved the cover of that book the minute I saw it, and began reading with the highest hopes, but I was already concerned just picking up the volume. The 1979 Selected ran to 339 pages; the 1995 Transbluesency, taking in decades more work to choose from, was 271 pages long.

Shortly after the publication, a retrospective symposium on Baraka's life and work was held at the Schomburg Library. One of the standout events of that weekend was a reading Baraka gave during which, at the suggestion of Kalamu ya Salaam, Baraka read poems from the entire breadth of his career, something I had never seen him do before and that I never again witnessed. Picking up Transbluesency, Baraka paused over the first poem on the first page and remarked, "there's a mistake here." That was just the beginning of it -- Transbluesency was badly marred by obvious typos and substantive errors. Any selection, like any anthology, is open to criticism for what has been omitted (or what perhaps should have been). I remember Kalamu asking Baraka why the book didn't include such powerful works as "I Investigate the Sun." But selection criteria aside, those of us who hope to teach from such books also hope to have reliable editions. Since 1995, Transbluesency has been the only easily acquired and adopted collection of Baraka's work spanning his writing life, and so I have often begun classes by issuing a corrections kit to my students so that we can all be on the same page with some assurance we are on a page Baraka wrote. Learning that the new SOS: Poems 1961-2013 was also being edited by Vangelisti, and that it was to be an expansion of Transbluesency, I harbored a wish that those many errors would be corrected.

And some of them have been -- That first poem, "Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note" has been corrected, but the fifth section of "Hymn for Lannie Poo" still contains lines that read "The preacher's / conning eyes / filed when he saw /the way I walked to- / wards him;" lines that don't really make much sense. "Conning eyes filed"? Readers of earlier editions know the word was supposed to be "fired." A pretty bad typo in "Wise I" has been corrected, but the opening page of "In the Tradition" retains a significant error. The current edition has the lines "the White Shadow / gives advice on how to hold our homes / together, tambien tu, Chicago Hermano" -- I imagine any number of readers have been wondering who this Chicago hermano is and why Baraka is addressing him in Spanish. Those of us who first heard the poem on the stunning LP New Music - New Poetry, accompanied by Fred Hopkins, Steve McCall and David Murray, know that the line goes "tu tambien, Chicano hermano." Chicano/Chicago -- not really a typo, and a world of difference.

Again, any of us might well have made a different selection. Why no "Why Is We Americans"? Why no "Something in the Way of Things," no "I Liked Us Better"? Was the decision to repeat exactly the selections from Transbluesency Baraka's choice? For the foreseeable future, we will have to live and work with these decisions. A proposed Collected was put on hold by Baraka's agents in favor of letting SOS have the field to itself for a time.

But it's not just copy editing that is a problem. The editor's introduction adds some new counterfactuals to those already circulating. Baraka's parents did not capitalize the "R" when they named him Everett Leroy Jones. It is simply not true that following 1973 Baraka "would only be published by smaller or alternative presses." That 1979 Selected (still a book to get on the used book market if you can't get all the original volumes)? That was published by Morrow, and it includes the Marxist period books Hard Facts and Poetry for the Advanced, the very sorts of work Vangelisti argues rendered Baraka unpublishable by the larger, commercial houses. Baraka often observed that it had been easier to get published with "hate whitey" than with "hate capitalism," and that is true enough. But that's a far cry from the claim advanced in the introduction to the new book. Morrow also published Baraka's Selected Plays and Prose and Daggers and Javelins, a major collection of essays from the Marxist period. It was also Morrow who published the first substantial collection of Baraka's later plays, The Motion of History. None of this is to take anything away from the story of Baraka's difficulties in the publishing world (part of why we haven't seen another major collection of the poems in all these years from a larger press), and we all owe a tremendous debt to Third World Press and the many small literary presses who continued to make Baraka's works available. Still, it's better to get the motion of history right when writing history, when you're editing the only large collection of Baraka's poetry that we're going to have for the foreseeable future.

There are questionable interpretations as well. Can we really make the case that Baraka's "lyrical realism" "sounds in counterpoint to his Beat contemporaries, steeped as they were in the egocentric idealism of nineteenth-century Anglo-American literature"? Take another look at Baraka's brilliant introduction to The Moderns and let his comments on the relationship of his contemporaries among the Beats to, say, Melville and Twain, sink in and then think carefully about this argument. And is it really defensible to claim that Baraka's writing is "both American (i.e., African American, of the 'New World') and firmly outside Anglo-American culture"?

On the other hand, Vangelisti is on much firmer ground with his observation that "up through the last poems, there remained above all a critical, often restless lyricism . . . " I think one of the greatest services this new volume will perform is forcing, or at least encouraging, a much more nuanced understanding of Baraka's later writings. The anthologies have tended to repeat the same few poems, and many readers, aided and abetted by America's publishing world, simply have no clue what Baraka's late poems are like. The image of a screaming, hate-filled nationalist was simply replaced in the national media imaginary by the image of a screaming, hate-filled communist (see the press controversy surrounding "Somebody Blew Up America" for a sense of what I'm getting at) and all too many critics and general readers alike simply didn't bother reading any poetry Baraka wrote over the past four decades. Those who did lay hands on copies of Funk Lore or Wise or any of the many chapbooks over the years knew that Baraka continued to write poetry easily the equal of anything done in his youth. How hard could it have been for anyone to know that? Still, it could have been a whole lot easier if he'd had the kind of book publication an Adrienne Rich or a Kevin Young or a Mark Strand seemed to find without quite so much trouble.

The final section of the new SOS, titled "Fashion This," is selected from work published after 1996 and is in itself cause for celebration, a truly important event in American poetry. Many familiar elements are in place. Where the young LeRoi Jones recollected the Green Lantern, the old Baraka at several points remembers the little devil cartoon character created by Gerald 2X in the pages of Muhammad Speaks. (Has anybody ever gathered those cartoons in one place?) The lyric reflections on Monk and Trane continued to Baraka's dying day. The scathing satire continued unabated. The wild experimentation with language went on (see "John Island Whisper"). The collection provides a new context for reading poems we've nearly talked to death in the past. Reread "Somebody Blew Up America?" next to Baraka's earlier poem written after the bombing in Oklahoma City.

There are few places in the work as deeply moving and lyrically intense as the poems for and about Amina Baraka, the former Sylvia Robinson. "What beauty is not anomalous / And strange"

If we ever do get a Collected Baraka (and let's hope it's also a corrected Baraka) I suspect it will need to be in two very large volumes, rather like the two volumes of the Creeley Collected we now have. There are at least 236 pages of uncollected poems just from the beginning of Baraka's publishing to 1966. Add to that all the uncollected poems since 1966 and whatever of the unpublished poetry can be coralled and you'd probably have another entire book at least as long as SOS. We need these books, but for now this is what we have. To the good, there is plenty here for us to reread and think over for a good long while.

The saddest lines in the entire 528 pages of SOS come in a late poem reflecting on late Auden: "What poetry does / is leave you when you stop needing it!" Poetry never left Amiri Baraka, and we will never stop needing his.

Long out of print, the Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, published in 1979, was advertised as "containing those poems which the author most wants to preserve," and that has long been the most substantial collection of Baraka's verse we had - 339 pages running from Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note through to Poetry for the Advanced. (This was the only volume in which many of us could find that second collection from Baraka's Marxist epoch.) There was no editor named in the book, so one assumes the selections are indeed Baraka's own.

A quarter century on, Marsilio published Transbluesency: Selected Poems 1961-1995, edited by Paul Vangelisti in consultation with the poet. I loved the cover of that book the minute I saw it, and began reading with the highest hopes, but I was already concerned just picking up the volume. The 1979 Selected ran to 339 pages; the 1995 Transbluesency, taking in decades more work to choose from, was 271 pages long.

Shortly after the publication, a retrospective symposium on Baraka's life and work was held at the Schomburg Library. One of the standout events of that weekend was a reading Baraka gave during which, at the suggestion of Kalamu ya Salaam, Baraka read poems from the entire breadth of his career, something I had never seen him do before and that I never again witnessed. Picking up Transbluesency, Baraka paused over the first poem on the first page and remarked, "there's a mistake here." That was just the beginning of it -- Transbluesency was badly marred by obvious typos and substantive errors. Any selection, like any anthology, is open to criticism for what has been omitted (or what perhaps should have been). I remember Kalamu asking Baraka why the book didn't include such powerful works as "I Investigate the Sun." But selection criteria aside, those of us who hope to teach from such books also hope to have reliable editions. Since 1995, Transbluesency has been the only easily acquired and adopted collection of Baraka's work spanning his writing life, and so I have often begun classes by issuing a corrections kit to my students so that we can all be on the same page with some assurance we are on a page Baraka wrote. Learning that the new SOS: Poems 1961-2013 was also being edited by Vangelisti, and that it was to be an expansion of Transbluesency, I harbored a wish that those many errors would be corrected.

And some of them have been -- That first poem, "Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note" has been corrected, but the fifth section of "Hymn for Lannie Poo" still contains lines that read "The preacher's / conning eyes / filed when he saw /the way I walked to- / wards him;" lines that don't really make much sense. "Conning eyes filed"? Readers of earlier editions know the word was supposed to be "fired." A pretty bad typo in "Wise I" has been corrected, but the opening page of "In the Tradition" retains a significant error. The current edition has the lines "the White Shadow / gives advice on how to hold our homes / together, tambien tu, Chicago Hermano" -- I imagine any number of readers have been wondering who this Chicago hermano is and why Baraka is addressing him in Spanish. Those of us who first heard the poem on the stunning LP New Music - New Poetry, accompanied by Fred Hopkins, Steve McCall and David Murray, know that the line goes "tu tambien, Chicano hermano." Chicano/Chicago -- not really a typo, and a world of difference.

Again, any of us might well have made a different selection. Why no "Why Is We Americans"? Why no "Something in the Way of Things," no "I Liked Us Better"? Was the decision to repeat exactly the selections from Transbluesency Baraka's choice? For the foreseeable future, we will have to live and work with these decisions. A proposed Collected was put on hold by Baraka's agents in favor of letting SOS have the field to itself for a time.

But it's not just copy editing that is a problem. The editor's introduction adds some new counterfactuals to those already circulating. Baraka's parents did not capitalize the "R" when they named him Everett Leroy Jones. It is simply not true that following 1973 Baraka "would only be published by smaller or alternative presses." That 1979 Selected (still a book to get on the used book market if you can't get all the original volumes)? That was published by Morrow, and it includes the Marxist period books Hard Facts and Poetry for the Advanced, the very sorts of work Vangelisti argues rendered Baraka unpublishable by the larger, commercial houses. Baraka often observed that it had been easier to get published with "hate whitey" than with "hate capitalism," and that is true enough. But that's a far cry from the claim advanced in the introduction to the new book. Morrow also published Baraka's Selected Plays and Prose and Daggers and Javelins, a major collection of essays from the Marxist period. It was also Morrow who published the first substantial collection of Baraka's later plays, The Motion of History. None of this is to take anything away from the story of Baraka's difficulties in the publishing world (part of why we haven't seen another major collection of the poems in all these years from a larger press), and we all owe a tremendous debt to Third World Press and the many small literary presses who continued to make Baraka's works available. Still, it's better to get the motion of history right when writing history, when you're editing the only large collection of Baraka's poetry that we're going to have for the foreseeable future.

There are questionable interpretations as well. Can we really make the case that Baraka's "lyrical realism" "sounds in counterpoint to his Beat contemporaries, steeped as they were in the egocentric idealism of nineteenth-century Anglo-American literature"? Take another look at Baraka's brilliant introduction to The Moderns and let his comments on the relationship of his contemporaries among the Beats to, say, Melville and Twain, sink in and then think carefully about this argument. And is it really defensible to claim that Baraka's writing is "both American (i.e., African American, of the 'New World') and firmly outside Anglo-American culture"?

On the other hand, Vangelisti is on much firmer ground with his observation that "up through the last poems, there remained above all a critical, often restless lyricism . . . " I think one of the greatest services this new volume will perform is forcing, or at least encouraging, a much more nuanced understanding of Baraka's later writings. The anthologies have tended to repeat the same few poems, and many readers, aided and abetted by America's publishing world, simply have no clue what Baraka's late poems are like. The image of a screaming, hate-filled nationalist was simply replaced in the national media imaginary by the image of a screaming, hate-filled communist (see the press controversy surrounding "Somebody Blew Up America" for a sense of what I'm getting at) and all too many critics and general readers alike simply didn't bother reading any poetry Baraka wrote over the past four decades. Those who did lay hands on copies of Funk Lore or Wise or any of the many chapbooks over the years knew that Baraka continued to write poetry easily the equal of anything done in his youth. How hard could it have been for anyone to know that? Still, it could have been a whole lot easier if he'd had the kind of book publication an Adrienne Rich or a Kevin Young or a Mark Strand seemed to find without quite so much trouble.

The final section of the new SOS, titled "Fashion This," is selected from work published after 1996 and is in itself cause for celebration, a truly important event in American poetry. Many familiar elements are in place. Where the young LeRoi Jones recollected the Green Lantern, the old Baraka at several points remembers the little devil cartoon character created by Gerald 2X in the pages of Muhammad Speaks. (Has anybody ever gathered those cartoons in one place?) The lyric reflections on Monk and Trane continued to Baraka's dying day. The scathing satire continued unabated. The wild experimentation with language went on (see "John Island Whisper"). The collection provides a new context for reading poems we've nearly talked to death in the past. Reread "Somebody Blew Up America?" next to Baraka's earlier poem written after the bombing in Oklahoma City.

There are few places in the work as deeply moving and lyrically intense as the poems for and about Amina Baraka, the former Sylvia Robinson. "What beauty is not anomalous / And strange"

If we ever do get a Collected Baraka (and let's hope it's also a corrected Baraka) I suspect it will need to be in two very large volumes, rather like the two volumes of the Creeley Collected we now have. There are at least 236 pages of uncollected poems just from the beginning of Baraka's publishing to 1966. Add to that all the uncollected poems since 1966 and whatever of the unpublished poetry can be coralled and you'd probably have another entire book at least as long as SOS. We need these books, but for now this is what we have. To the good, there is plenty here for us to reread and think over for a good long while.

The saddest lines in the entire 528 pages of SOS come in a late poem reflecting on late Auden: "What poetry does / is leave you when you stop needing it!" Poetry never left Amiri Baraka, and we will never stop needing his.

Tender Arrivals

by Amiri Baraka

Where ever something breathes

Heart beating the rise and fall

Of mountains, the waves upon the sky

Of seas, the terror is our ignorance, that’s

Why it is named after our home, earth

Where art is locked between

Gone and Destination

The destiny of some other where and feeling

The ape knew this, when his old lady pulled him up

Off the ground. Was he grateful, ask him he’s still sitting up there

Watching the sky’s adventures, leaving two holes for his own. Oh sing

Gigantic burp past the insects, swifter than the ugly Stanleys on the ground

Catching monkey meat for Hyenagators, absolute boss of what does not

Arrive in time to say anything. We hear that eating, that doo dooing, that

Burping, we had a nigro mayor used to burp like poison zapalote

Waddled into the cave of his lust. We got a Spring Jasper now, if

you don’t like that

woid, what about courtesan, dreamed out his own replacement sprawled

Across the velvet cash register of belching and farting, his knick names when they

let him be played with. Some call him Puck, was love, we thought, now a rubber

Flat blackie banged across the ice, to get past our Goli, the Africannibus of memory.

Here. We have so many wedged between death and passivity. Like eyes that collide

With reality and cannot see anything but the inner abstraction of flatus, a

biography, a car, a walk to the guillotine, James the First, Giuliani the Second

When he tries to go national, senators will stab him, Ides of March or Not. Maybe

Both will die, James 1 and Caesar 2, as they did in the past, where we can read about

The justness of their assassinations

As we swig a little brew and laugh at the perseverance

Of disease at higher and higher levels of its elimination.

We could see anything we wanted to. Be anything we knew how to be. Build

anything we needed. Arrive anywhere we should have to go. But time is as stubborn

as space, and they compose us with definition, time place and condition.

The howlees the yowlees the yankees the super left streamlined post racial ideational

chauvinists creeep at the mouth of the venal cava. They are protesting fire and

Looking askance at the giblets we have learned to eat. “It’s nobody’s heart,” they

say, and we agree. It’s the rest of some thing’s insides. Along with the flowers, the

grass, the tubers, the river, pieces of the sky, earth, our seasoning, baked

throughout. What do you call that the anarchist of comfort asks,

Food, we say, making it up as we chew. Yesterday we explained language.

“Tender Arrivals” printed in S O S: POEMS 1961–2013 © 2014 by The Estate of Amiri Baraka; collection edited by Paul Vangelisti; used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc.

Source: Poetry (February 2015).

by Amiri Baraka

Where ever something breathes

Heart beating the rise and fall

Of mountains, the waves upon the sky

Of seas, the terror is our ignorance, that’s

Why it is named after our home, earth

Where art is locked between

Gone and Destination

The destiny of some other where and feeling

The ape knew this, when his old lady pulled him up

Off the ground. Was he grateful, ask him he’s still sitting up there

Watching the sky’s adventures, leaving two holes for his own. Oh sing

Gigantic burp past the insects, swifter than the ugly Stanleys on the ground

Catching monkey meat for Hyenagators, absolute boss of what does not

Arrive in time to say anything. We hear that eating, that doo dooing, that

Burping, we had a nigro mayor used to burp like poison zapalote

Waddled into the cave of his lust. We got a Spring Jasper now, if

you don’t like that

woid, what about courtesan, dreamed out his own replacement sprawled

Across the velvet cash register of belching and farting, his knick names when they

let him be played with. Some call him Puck, was love, we thought, now a rubber

Flat blackie banged across the ice, to get past our Goli, the Africannibus of memory.

Here. We have so many wedged between death and passivity. Like eyes that collide

With reality and cannot see anything but the inner abstraction of flatus, a

biography, a car, a walk to the guillotine, James the First, Giuliani the Second

When he tries to go national, senators will stab him, Ides of March or Not. Maybe

Both will die, James 1 and Caesar 2, as they did in the past, where we can read about

The justness of their assassinations

As we swig a little brew and laugh at the perseverance

Of disease at higher and higher levels of its elimination.

We could see anything we wanted to. Be anything we knew how to be. Build

anything we needed. Arrive anywhere we should have to go. But time is as stubborn

as space, and they compose us with definition, time place and condition.

The howlees the yowlees the yankees the super left streamlined post racial ideational

chauvinists creeep at the mouth of the venal cava. They are protesting fire and

Looking askance at the giblets we have learned to eat. “It’s nobody’s heart,” they

say, and we agree. It’s the rest of some thing’s insides. Along with the flowers, the

grass, the tubers, the river, pieces of the sky, earth, our seasoning, baked

throughout. What do you call that the anarchist of comfort asks,

Food, we say, making it up as we chew. Yesterday we explained language.

“Tender Arrivals” printed in S O S: POEMS 1961–2013 © 2014 by The Estate of Amiri Baraka; collection edited by Paul Vangelisti; used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc.

Source: Poetry (February 2015).