The Other Blacklist: The African American Literary and Cultural Left of the 1950s

by Mary Helen Washington

by Mary Helen Washington

Hardcover: 368 pages

Publisher: Columbia University Press

April 8, 2014

ISBN-10: 0231152701

ISBN-13: 978-0231152709

Editorial Reviews:

From Booklist

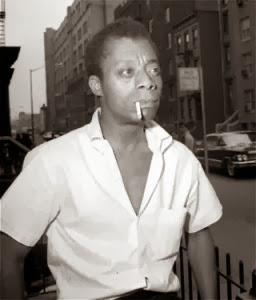

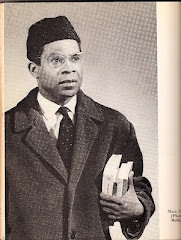

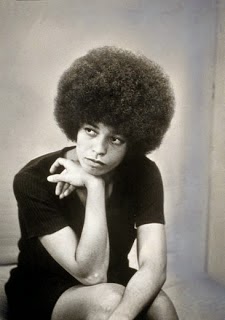

*Starred Review* Considering that any effort to achieve racial equality was viewed as subversive in the Cold War era, is it any wonder that so many black artists and writers were viewed as Communists? Yet very little has been written about the black artists and writers who were surveilled, investigated, and blacklisted because of their beliefs and their work. Literary scholar Washington remedies that neglect with this engrossing look at six artists. Though some were Communist Party members and others not, they were all drawn to the Left’s appreciation of black folk culture and support for the ideal of self-determination, themes that figured prominently in their work. Washington profiles novelist and essayist Lloyd L. Brown, visual artist Charles White, playwright and novelist Alice Childress, poet and novelist Gwendolyn Brooks, novelist Frank London Brown, and novelist and activist Julian Mayfield. Tapping archival material, biographies, interviews, and FBI files, Washington examines his subjects’ aesthetic and relationships with other writers and artists and the black community as well as their frustrations with and ambivalent feelings about the Left. Photographs of the artists and their works and pages from FBI files enhance this compelling look at artists and writers who became part of the vanguard of the progressive politics and civil rights movement of the 1960s. --Vanessa Bush

Review

ISBN-13: 978-0231152709

Editorial Reviews:

From Booklist

*Starred Review* Considering that any effort to achieve racial equality was viewed as subversive in the Cold War era, is it any wonder that so many black artists and writers were viewed as Communists? Yet very little has been written about the black artists and writers who were surveilled, investigated, and blacklisted because of their beliefs and their work. Literary scholar Washington remedies that neglect with this engrossing look at six artists. Though some were Communist Party members and others not, they were all drawn to the Left’s appreciation of black folk culture and support for the ideal of self-determination, themes that figured prominently in their work. Washington profiles novelist and essayist Lloyd L. Brown, visual artist Charles White, playwright and novelist Alice Childress, poet and novelist Gwendolyn Brooks, novelist Frank London Brown, and novelist and activist Julian Mayfield. Tapping archival material, biographies, interviews, and FBI files, Washington examines his subjects’ aesthetic and relationships with other writers and artists and the black community as well as their frustrations with and ambivalent feelings about the Left. Photographs of the artists and their works and pages from FBI files enhance this compelling look at artists and writers who became part of the vanguard of the progressive politics and civil rights movement of the 1960s. --Vanessa Bush

Review

"A wonderful combination of careful research, adept historicizing, and insightful close reading. Mary Helen Washington's book brings needed critical attention to understudied figures and helps readers rethink the careers of others whom they believe they already know."

(James Smethurst, author of The African American Roots of Modernism: From Reconstruction to the Harlem Renaissance and The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s)

"[A] compelling look at artists and writers who became part of the vanguard of the progressive politics and civil rights movement of the 1960s."

(Booklist (starred review))

"Groundbreaking...thought-provoking."

(Publishers Weekly (starred review))

See all Editorial Reviews

Review

"A groundbreaking and eye-opening study. In Washington's sure hands, biography, politics, and cultural history combine to open new intellectual vistas."

(Alan M. Wald, University of Michigan)

About the Author

(James Smethurst, author of The African American Roots of Modernism: From Reconstruction to the Harlem Renaissance and The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s)

"[A] compelling look at artists and writers who became part of the vanguard of the progressive politics and civil rights movement of the 1960s."

(Booklist (starred review))

"Groundbreaking...thought-provoking."

(Publishers Weekly (starred review))

See all Editorial Reviews

Review

"A groundbreaking and eye-opening study. In Washington's sure hands, biography, politics, and cultural history combine to open new intellectual vistas."

(Alan M. Wald, University of Michigan)

About the Author

Mary Helen Washington is a professor in the English Department at the University of Maryland, College Park. She has been a Bunting Fellow at Harvard University and has taught at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She is the editor of Black-Eyed Susans: Classic Stories by Black Women Writers; Midnight Birds: Stories of Contemporary Black Women Writers; Invented Lives: Narratives of Black Women; and Memory of Kin: Stories of Family by Black Writers.

https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-15270-9/the-other-blacklist

The Other Blacklist: The African American Literary and Cultural Left of the 1950s

by Mary Helen Washington

Columbia University Press

April, 2014

Cloth, 368 pages, B & W Photos: 28

ISBN: 978-0-231-15270-9

$35.00 / £24.00

Mary Helen Washington recovers the vital role of 1950s leftist politics in the works and lives of modern African American writers and artists. While most histories of McCarthyism focus on the devastation of the blacklist and the intersection of leftist politics and American culture, few include the activities of radical writers and artists from the Black Popular Front. Washington’s work incorporates these black intellectuals back into our understanding of mid-twentieth-century African American literature and art and expands our understanding of the creative ferment energizing all of America during this period.

Mary Helen Washington reads four representative writers—Lloyd Brown, Frank London Brown, Alice Childress, and Gwendolyn Brooks—and surveys the work of the visual artist Charles White. She traces resonances of leftist ideas and activism in their artistic achievements and follows their balanced critique of the mainstream liberal and conservative political and literary spheres. Her study recounts the targeting of African American as well as white writers during the McCarthy era, reconstructs the events of the 1959 Black Writers’ Conference in New York, and argues for the ongoing influence of the Black Popular Front decades after it folded. Defining the contours of a distinctly black modernism and its far-ranging radicalization of American politics and culture, Washington fundamentally reorients scholarship on African American and Cold War literature and life.

Related Subjects

American History

American Literature

Art History

Literary Criticism and Theory

About the Author

Mary Helen Washington is a professor in the English Department at the University of Maryland, College Park. She has been a Bunting Fellow at Harvard University and has taught at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She is the editor of Black-Eyed Susans: Classic Stories by Black Women Writers; Midnight Birds: Stories of Contemporary Black Women Writers; Invented Lives: Narratives of Black Women; and Memory of Kin: Stories of Family by Black Writers.

New Malcolm X Diary Reveals a Revolutionary Optimist

On the 50th anniversary of the founding of his Organization of Afro-American Unity, Malcolm X’s powerful ties to Africa and African leaders are explored.

BY TODD STEVEN BURROUGHS

July 1, 2014

The Root

On the 50th anniversary of the founding of his Organization of Afro-American Unity, Malcolm X’s powerful ties to Africa and African leaders are explored.

BY TODD STEVEN BURROUGHS

July 1, 2014

The Root

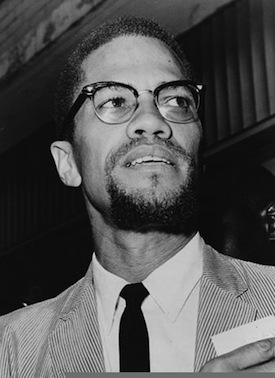

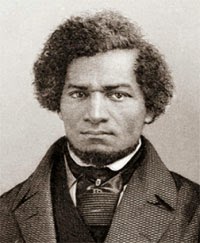

Malcolm X on March 26, 1964

U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT MAGAZINE PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT MAGAZINE PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

While many in the civil rights movement community this summer are celebrating the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, another important half-century milestone—and a significantly blacker, more radical one—was recently acknowledged in New York City: the founding of the Organization of Afro-American Unity, Malcolm X’s political organization.

If Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of domestic social equality turned into a nightmare, Malcolm’s vision for black Americans to join the international community of Africans as an anti-Western bloc was quickly stifled with his 1965 assassination. The OAAU—patterned after the OAU, the Organization of African Unity—represented Malcolm’s domestic and international potential, a painful addition to the pile of 20th-century black historical what-ifs.

“Brother Malcolm was internationalizing the movement,” said event organizer A. Peter Bailey, who was only in his early 20s when he edited the OAAU’s newsletter, The Blacklash. “He was on a conscious effort to connect the struggle against racism in America to the struggle against colonialism internationally, especially in Africa.”

The OAAU event, which took place on June 28—the to-the-day 50th anniversary—at the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center (the former Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm was assassinated), came in the wake of a newly published diary of Malcolm X. The book, edited by journalist-historian Herb Boyd and writer Ilyasah Al-Shabazz, one of Malcolm X’s six daughters, is called The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, 1964. Finally freed from scholarly microfilm, the diary has been the subject of a court case between the authors and the publisher, Third World Press, and Malcolm’s other five daughters, who did not sign off on the book’s publication.

Malcolm’s diary paints the picture of a man eager to find his religious and political centers. Most of the first half of the book details his much-talked-about trip to Mecca in Saudi Arabia, while the second half—which takes place after the OAAU founding in New York—is more about his travels to Africa, where he meets more than 10 heads of state and is treated like a de facto ambassador of black America.

He had multiple goals: to educate the African leaders about the plight of African Americans; to get African leaders to denounce the United States because of Jim Crow and its accompanied violence, with the possibility of bringing the U.S. before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights; and to unite the Muslim and African worlds against Western imperialism, especially what Malcolm called “dollarism,” the funds the U.S. gave out to help, and ultimately silence, much of the Third World during the Cold War.

Malcolm was not allowed to address the 1964 OAU meeting in Cairo, but he did write and pass around a memorandum there detailing American racism. The OAU, in turn, did release a public condemnation of the United States for its treatment of African Americans.

“I find all the African delegates at all levels are strongly sympathetic to our cause,” he writes in a Wednesday, July 15, entry. “But American propaganda through the USIS [United States Information Service] has been powerful[,] influencing most of them to think we hate Africa & don’t identify with her in any way. Most of them are shocked by my strongly pro-African sentiments—shocked and elated.”

Bailey, who has written a new memoir of his time with Malcolm X, called Witnessing Brother Malcolm X, the Master Teacher: A Memoir, says of the period, “J. Edgar Hoover turned green when he heard of that [OAU] resolution.” He emphasized that Malcolm, whom he called a master of propaganda, stuck a needle in the eye of the United States with that act, making it harder for America to be seen as a bastion of democracy.

“He [Malcolm] was a black nationalist. He said it enough times,” said former OAAU member Earl Grant, now 84. “He was what people today would probably call an African nationalist.” Malcolm, said Grant, was in the tradition of black human rights activists such as back-to-Africa preacher Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, the crusading journalist and suffragist Ida B. Wells, and the proto-Garveyite intellectual Hubert Henry Harrison.

The New York City event, during which letters and documents of the OAAU’s tenure were read, had a feeling of radical, analog nostalgia. It was both quaint and important to briefly revisit the days when people wrote and mailed letters and had telephone-exchange names. The period was one of great optimism, when all parts of the movement, radical to moderate, thought they were going to win and reshape America and the world in some fashion.

The OAAU and the diary were both part of that ’60s revolutionary optimism. The OAAU was much more than a paper organization but less than a fully functional protest group. The diary, as a collection of literal notes, gives us important insights not only into Malcolm’s thinking but also into his militant, anti-Western, anti-imperialist actions.

The more that can be learned about Malcolm’s domestic and international political goals, the less it will be said that all he did was make speeches in Harlem while others in the movement did concrete work. As black America approaches the 50th anniversary of his assassination next Feb. 21, these clarifying details can allow for much-needed new discussions about Malcolm now and beyond.

Todd Steven Burroughs, co-editor, with Jared Ball, of A Lie of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X, is a freelance writer based in Hyattsville, Md. He has taught at Morgan State and Howard universities. He can be reached at toddpanther@gmail.com.

Like The Root on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.

If Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of domestic social equality turned into a nightmare, Malcolm’s vision for black Americans to join the international community of Africans as an anti-Western bloc was quickly stifled with his 1965 assassination. The OAAU—patterned after the OAU, the Organization of African Unity—represented Malcolm’s domestic and international potential, a painful addition to the pile of 20th-century black historical what-ifs.

“Brother Malcolm was internationalizing the movement,” said event organizer A. Peter Bailey, who was only in his early 20s when he edited the OAAU’s newsletter, The Blacklash. “He was on a conscious effort to connect the struggle against racism in America to the struggle against colonialism internationally, especially in Africa.”

The OAAU event, which took place on June 28—the to-the-day 50th anniversary—at the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center (the former Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm was assassinated), came in the wake of a newly published diary of Malcolm X. The book, edited by journalist-historian Herb Boyd and writer Ilyasah Al-Shabazz, one of Malcolm X’s six daughters, is called The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, 1964. Finally freed from scholarly microfilm, the diary has been the subject of a court case between the authors and the publisher, Third World Press, and Malcolm’s other five daughters, who did not sign off on the book’s publication.

Malcolm’s diary paints the picture of a man eager to find his religious and political centers. Most of the first half of the book details his much-talked-about trip to Mecca in Saudi Arabia, while the second half—which takes place after the OAAU founding in New York—is more about his travels to Africa, where he meets more than 10 heads of state and is treated like a de facto ambassador of black America.

He had multiple goals: to educate the African leaders about the plight of African Americans; to get African leaders to denounce the United States because of Jim Crow and its accompanied violence, with the possibility of bringing the U.S. before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights; and to unite the Muslim and African worlds against Western imperialism, especially what Malcolm called “dollarism,” the funds the U.S. gave out to help, and ultimately silence, much of the Third World during the Cold War.

Malcolm was not allowed to address the 1964 OAU meeting in Cairo, but he did write and pass around a memorandum there detailing American racism. The OAU, in turn, did release a public condemnation of the United States for its treatment of African Americans.

“I find all the African delegates at all levels are strongly sympathetic to our cause,” he writes in a Wednesday, July 15, entry. “But American propaganda through the USIS [United States Information Service] has been powerful[,] influencing most of them to think we hate Africa & don’t identify with her in any way. Most of them are shocked by my strongly pro-African sentiments—shocked and elated.”

Bailey, who has written a new memoir of his time with Malcolm X, called Witnessing Brother Malcolm X, the Master Teacher: A Memoir, says of the period, “J. Edgar Hoover turned green when he heard of that [OAU] resolution.” He emphasized that Malcolm, whom he called a master of propaganda, stuck a needle in the eye of the United States with that act, making it harder for America to be seen as a bastion of democracy.

“He [Malcolm] was a black nationalist. He said it enough times,” said former OAAU member Earl Grant, now 84. “He was what people today would probably call an African nationalist.” Malcolm, said Grant, was in the tradition of black human rights activists such as back-to-Africa preacher Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, the crusading journalist and suffragist Ida B. Wells, and the proto-Garveyite intellectual Hubert Henry Harrison.

The New York City event, during which letters and documents of the OAAU’s tenure were read, had a feeling of radical, analog nostalgia. It was both quaint and important to briefly revisit the days when people wrote and mailed letters and had telephone-exchange names. The period was one of great optimism, when all parts of the movement, radical to moderate, thought they were going to win and reshape America and the world in some fashion.

The OAAU and the diary were both part of that ’60s revolutionary optimism. The OAAU was much more than a paper organization but less than a fully functional protest group. The diary, as a collection of literal notes, gives us important insights not only into Malcolm’s thinking but also into his militant, anti-Western, anti-imperialist actions.

The more that can be learned about Malcolm’s domestic and international political goals, the less it will be said that all he did was make speeches in Harlem while others in the movement did concrete work. As black America approaches the 50th anniversary of his assassination next Feb. 21, these clarifying details can allow for much-needed new discussions about Malcolm now and beyond.

Todd Steven Burroughs, co-editor, with Jared Ball, of A Lie of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X, is a freelance writer based in Hyattsville, Md. He has taught at Morgan State and Howard universities. He can be reached at toddpanther@gmail.com.

Like The Root on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.