MILES DEWEY DAVIS III

(b. May 26,1926--d. September 28, 1991)

(b. May 26,1926--d. September 28, 1991)

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on May 26, 2008):

Monday, May 26, 2008

LONG LIVE MILES DAVIS: May 26, 1926--September 28, 1991

All,

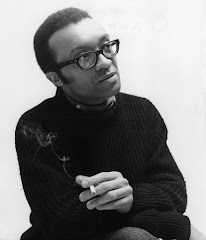

In recognition of the glorious and extraordinary art of one of the greatest and most important artists of the 20th century this magazine celebrates the 82th birthday of the musical legend known as Miles Dewey Davis III. For an extended critical and celebratory examination of his life and work please consult the following links below, including this essay by myself that was originally posted on this site on February 23, 2008. The following links contain many film clips and various articles, reviews, and essays about Miles Davis as well as an extended excerpt of Miles talking about his storied life and career in his own words and voice from his acclaimed autobiography published in 1989 and co-authored by poet, critic, and cultural historian Quincy Troupe. There is also a section of some famous (and infamous quotes) by Davis, who was as well known in many circles for his erudite and insightful commentary, wicked barbs, and often caustic and witty aphorisms as he was for his visionary and highly innovative musicianship on the trumpet. HAPPY BIRTHDAY MILES!

(Originally posted on May 26, 2008):

Monday, May 26, 2008

LONG LIVE MILES DAVIS: May 26, 1926--September 28, 1991

All,

In recognition of the glorious and extraordinary art of one of the greatest and most important artists of the 20th century this magazine celebrates the 82th birthday of the musical legend known as Miles Dewey Davis III. For an extended critical and celebratory examination of his life and work please consult the following links below, including this essay by myself that was originally posted on this site on February 23, 2008. The following links contain many film clips and various articles, reviews, and essays about Miles Davis as well as an extended excerpt of Miles talking about his storied life and career in his own words and voice from his acclaimed autobiography published in 1989 and co-authored by poet, critic, and cultural historian Quincy Troupe. There is also a section of some famous (and infamous quotes) by Davis, who was as well known in many circles for his erudite and insightful commentary, wicked barbs, and often caustic and witty aphorisms as he was for his visionary and highly innovative musicianship on the trumpet. HAPPY BIRTHDAY MILES!

Kofi

http://www.milesdavis.com/bio.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_discography.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_various.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_options.asp

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miles_Davi http://www.geocities.com/Heartland/Valley/2822/miles_davis.html http://www.rockhall.com/inductee/miles-davis http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_davis_miles.htm http://www.plosin.com/milesAhead/mdBibliography.html http://www.jazzitude.com/miles_jackjohnsoncomplete01.htm

http://www.milesdavis.com/bio.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_discography.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_various.asp

http://www.milesdavis.com/music_options.asp

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miles_Davi http://www.geocities.com/Heartland/Valley/2822/miles_davis.html http://www.rockhall.com/inductee/miles-davis http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_davis_miles.htm http://www.plosin.com/milesAhead/mdBibliography.html http://www.jazzitude.com/miles_jackjohnsoncomplete01.htm

MILES DAVIS SPEAKING:

"Sometimes you have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself."

"Don't play what's there, play what's not there."

"For me, music and life are all about style."

"I know what I've done for music, but don't call me a legend. Just call me Miles Davis."

"I'll play it and tell you what it is later."

"I'm always thinking about creating. My future starts when I wake up every morning... Every day I find something creative to do with my life."

"If you understood everything I say, you'd be me!"

"It's always been a gift with me, hearing music the way I do. I don't know where it comes from, it's just there and I don't question it."

"The thing to judge in any jazz artist is, does the man project and does he have ideas."

"It took me twenty years to be able to play that note and you want to understand everything I do in five minutes?"

"I have to change. It's like a curse"

"Sometimes you have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself."

"Don't play what's there, play what's not there."

"For me, music and life are all about style."

"I know what I've done for music, but don't call me a legend. Just call me Miles Davis."

"I'll play it and tell you what it is later."

"I'm always thinking about creating. My future starts when I wake up every morning... Every day I find something creative to do with my life."

"If you understood everything I say, you'd be me!"

"It's always been a gift with me, hearing music the way I do. I don't know where it comes from, it's just there and I don't question it."

"The thing to judge in any jazz artist is, does the man project and does he have ideas."

"It took me twenty years to be able to play that note and you want to understand everything I do in five minutes?"

"I have to change. It's like a curse"

Miles Ahead: Bibliography

Chris Albertson, "The Unmasking of Miles Davis," Saturday Review, November 27, 1971, pp. 67-87 (with interruptions).

Frank Alkyer, "The Miles Files," Down Beat, December 1991, pp. 22-24.

------ (ed.), The Miles Davis Reader. New York: Hal Leonard, 2007.

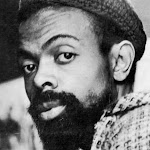

Amiri Baraka, "Miles Davis: One of the Great Mother Fuckers," in Amiri and Amina Baraka (edd.), The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues. New York: William Morrow, 1987, pp. 290-301.

Bob Belden and John Ephland, "Miles... What was that note?" Down Beat, December 1995, pp. 17-22.

Ian Carr, Miles Davis: A Biography. New York: Morrow, 1982.

Franck Bergerot, Miles Davis: introduction a l'ecoute du jazz moderne, editions du Seuil, Paris, 1996.

Luca Bragalini, "Miles Davis e la Disgregazione dello Standard, parts 1-2" Musica Jazz, 53/9 (Agosto-Settembre 1997) and 53/10 (Ottobre 1997). An English translation is available on this website.

Howard Brofsky, "Miles Davis and My Funny Valentine: The Evolution of a Solo," Black Music Research Journal 3, Winter 1983, pp. 23-34.

Gary Carner, The Miles Davis Companion: Four Decades of Commentary. New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

Ian Carr, Miles Davis: A Critical Biography. New York: Morrow, 1982; London: Quartet Books, 1982.

Jack Chambers, Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998. Previously published by Quill/Morrow, 1989. Originally published in two volumes, 1983 and 1985.

Bill Cole, Miles Davis: The Early Years. New York: Da Capo Press, 1994.

George Cole, The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis, 1980-1991. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Todd Coolman, The Miles Davis Quintet of the Mid-1960s: Synthesis of Improvisational and Compositional Elements. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1997.

Julie Coryell and Laura Friedman, Jazz-Rock Fusion: The People, The Music. New York: Delta Books, 1978.

Laurent Cugny, Electrique Miles Davis 1968-1975. Marseille: André Dimanche Éditeur, 1993.

Michael Cuscuna and Michel Ruppli, The Blue Note Label: A Discography. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Miles Davis with Scott Gutterman, The Art of Miles Davis. New York: Prentice Hall Editions, 1991.

Scott DeVeaux, The Birth of Bebop: A Social and Musical History. Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1997.

Chris DeVito, Yasuhiro Fujioka, Wolf Schmaler, David Wild, edited by Lewis Porter, The John Coltrane Reference. New York and London: Taylor and Francis, 2008.

Gerald Early (ed.), Miles Davis and American Culture. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2001.

Leonard Feather, "Miles and the Fifties" (Classic Interview), Down Beat, March 1995, pp. 36-39. (Interview originally appeared in Down Beat July 2, 1964.)

Leonard Feather and Miles Davis, "Blindfold Test." Davis did five Blindfold Tests with Feather in Down Beat magazine: September 21, 1955 (pp. 33-34); August 7, 1958 (p. 29); June 18, 1964 (p. 21); June 13, 1968 (p. 34); and June 27, 1968 (p. 33).

Larry Fisher, Miles Davis and Dave Liebman: Jazz Connections. Stroudsberg: CARIS Music Services, 1999.

Yasuhiro Fujioka, Lewis Porter, and Yoh-Ichi Hamada, John Coltrane: A Discography and Musical Biography. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995. Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies, Studies in Jazz, Volume 20.

Ralph J. Gleason, "Miles Davis," Rolling Stone, December 13, 1969.

Frederic Goaty, Miles Davis, Editions Vade Retro, Paris, 1995.

Gregg Hall, "Miles Davis: Today's Most Influential Contemporary Musician," Down Beat, July 18, 1974, pp. 16-20.

Alex Haley, "The Miles Davis Interview," Playboy, September 1962.

Max Harrison, "Sheer Alchemy, for a While: Miles Davis and Gil Evans," Jazz Monthly, December 1958 and Febraury 1960.

Don Heckman, "Miles Davis Times Three: The Evolution of a Jazz Artist," Down Beat, August 30, 1962, pp. 16-19.

Michael James, Miles Davis. London: Faber and Cassell, 1961.

Ashley Kahn, Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. New York: Da Capo Press, 2000.

Barry Kernfield, Adderley, Coltrane, and Davis at the Twilight of Bop: The Search for Melodic Coherence (1958-1959). Ann Arbor: University Microfilems, 1981.

Bill Kirchner (ed.), A Miles Davis Reader (Smithsonian Readers in American Music). Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997.

Jan Lohmann, The Sound of Miles Davis: The Discography 1945-1991. Copenhagen: JazzMedia ApS, 1991.

Daryl Long, Miles Davis For Beginners. New York: Writers and Readers, 1994.

Jeffrey Magee, "Kinds of Blue: Miles Davis, Afro-Modernism, and the Blues," Jazz Perspectives vol. 1, no. 1 (May 2007): 5-27.

Howard Mandel, "Sketches of Miles," Down Beat, December 1991, pp. 16-20.

Barry McRae, Miles Davis. London: Apollo Books, 1988.

Dan Morgenstern, "Miles in Motion," Down Beat, September 3, 1970, pp. 16-17.

Yasuki Nakayama, Miles Davis Complete Discography. Tokyo: Futabasha, 2000.

------, Listen to Miles, Version 6. Tokyo: Futabasha, 2004.

------, Miles Davis: We Love Music, We Love the Earth. Tokyo: Tokyo FM, 2002.

Eric Nisenson, 'Round About Midnight: A Portrait of Miles Davis. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Tore Mortensen, Miles Davis: Den Ny Jazz. Aarhus: n/a, 1976.

Chris Murphy, Miles to Go: The Later Years. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 2002.

Takao Ogawa a.o., Jazz Hero's Data Bank. Tokyo: JICC, 1991.

Toyoki Okajima (ed.), The Complete Blue Note Book: Tribute to Alfred Lion. Jazz Critique Special Edition, No. 3 (1987). Tokyo: Jazz Hihyo, 1987.

------, The Prestige Book: Discography of All Series. Jazz Critique Special Edition No. 3 (1996). Tokyo: Jazz Hihyo, 1996.

Harvey Pekar, "Miles Davis: 1964-69 Recordings," Coda, May 1976, pp. 8-14.

Bret Primack, "Remembering Miles," Jazz Times, February 1992, pp. 17-88 (with interruptions).

Michel Ruppli and Bob Porter, The Prestige Label: A Discography. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1980.

Michel Ruppli and Bob Porter, The Savoy Label: A Discography. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1980.

Jimmy Saunders, "An Interview with Miles Davis," Playboy, April 1975.

R.B. Shaw, "Miles Above," Jazz Journal, November 1960, pp. 15-16.

Chris Smith, "A Sense of the Possible: Miles Davis and the Semiotics of Improvised Performance", in In the Course of Performance: Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation (edd. Bruno Nett and Melinda Russell), University of Chicago Press, 1998.

John Szwed, So What: The Life of Miles Davis. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002.

Greg Tate, "The Electric Miles: Parts 1 and 2," Down Beat, July and August 1983.

Paul Tingen, Miles Beyond: Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991. New York: Billboard Books, 2001.

Gary Tomlinson, "Miles Davis: Musical Dialogician," Black Music Research Journal 11/2, Fall 1991, pp. 249-64.

Ken Vail, Miles' Diary: The Life of Miles Davis, 1947-1961. London: Sanctuary Publishing, 1996.

Robert Walser, "Out of Notes: Signification, Interpretation, and the Problem of Miles Davis," Musical Quarterly, Summer 1993, pp. 343-65.

Peter Weissmüller, Miles Davis: Sein Leben, Musik, Schallplatten. Berlin: OREOS, 1988.

Richard Williams, The Man in The Green Shirt. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993.

Posted by Kofi Natambu at 4:21 PM

Labels: 20th century Art, American Culture, Jazz history, Miles Davis

Upper West Side Street Renamed in Miles Davis' Honor

By: Jon Weinstein

5/26/2014

NY1 News

Legendary musician Miles Davis' name will now forever be tied to the Manhattan street he called home. NY1's Jon Weinstein filed the following report.

The familiar sounds of Miles Davis' famous trumpet filled 77th Street on what would have been his 88th birthday.

Hundreds turned out to rename this block after the musician.

And just how excited was everyone?

After a string snafu during the street sign unveiling, one enterprising and athletic fan climbed the lamp post to make sure this stretch between Riverside and West End officially became Miles Davis Way.

"This is where the seminal pieces of music were rehearsed. You know, the quintet was here. We did a record here with man with the horn. It's like what Graceland is to Elvis, this is to Miles Davis: Miles Davis Way," said Vince Wilburn, Jr., Miles Davis' Nephew.

Davis lived on this block and made some of his most memorable music as a resident of the Upper West Side.

The jazz legends who got the chance to play with Davis say this is an honor he deserved.

Miles Davis was not only a legend but he was a trendsetter in terms of pushing the envelope," said jazz musician Bobbi Humphrey.

"He was a pioneer in the change in music. He kept evolving," said jazz musician Jimmy Heath.

"New York is the place where everybody wants to come because they say if you make it here, you make it anywhere. So Miles came here and made it big," drummer Jimmy Cobb said.

Davis' children say he was inspired by life in the city and even though he wasn't born here, this is a place he always called home.

"This is kind of like when we think of Miles in New York, we think of 77th," said Erin Davis, Miles Davis' Son.

"He thought the sounds of New York were musical to him in different ways and that's how he used it in his music and in his profession," said Miles Davis' daughter Cheryl Davis.

For the fans, this was a chance to come together to celebrate his life and make sure his music is never forgotten.

"He never stood still, his music keep moving,"

"This is what New York is about. New York is Miles Davis,"

Now, there is a permanent reminder of that famous connection between the city and the legendary musician.

http://www.milesdavis.com/fr/node/18615

NYC BLOCK PARTY CELEBRATES OFFICIAL UNVEILING OF 'MILES DAVIS WAY' ON THE 88th BIRTHDAY OF MILES DAVIS

By: Jon Weinstein

5/26/2014

NY1 News

Legendary musician Miles Davis' name will now forever be tied to the Manhattan street he called home. NY1's Jon Weinstein filed the following report.

The familiar sounds of Miles Davis' famous trumpet filled 77th Street on what would have been his 88th birthday.

Hundreds turned out to rename this block after the musician.

And just how excited was everyone?

After a string snafu during the street sign unveiling, one enterprising and athletic fan climbed the lamp post to make sure this stretch between Riverside and West End officially became Miles Davis Way.

"This is where the seminal pieces of music were rehearsed. You know, the quintet was here. We did a record here with man with the horn. It's like what Graceland is to Elvis, this is to Miles Davis: Miles Davis Way," said Vince Wilburn, Jr., Miles Davis' Nephew.

Davis lived on this block and made some of his most memorable music as a resident of the Upper West Side.

The jazz legends who got the chance to play with Davis say this is an honor he deserved.

Miles Davis was not only a legend but he was a trendsetter in terms of pushing the envelope," said jazz musician Bobbi Humphrey.

"He was a pioneer in the change in music. He kept evolving," said jazz musician Jimmy Heath.

"New York is the place where everybody wants to come because they say if you make it here, you make it anywhere. So Miles came here and made it big," drummer Jimmy Cobb said.

Davis' children say he was inspired by life in the city and even though he wasn't born here, this is a place he always called home.

"This is kind of like when we think of Miles in New York, we think of 77th," said Erin Davis, Miles Davis' Son.

"He thought the sounds of New York were musical to him in different ways and that's how he used it in his music and in his profession," said Miles Davis' daughter Cheryl Davis.

For the fans, this was a chance to come together to celebrate his life and make sure his music is never forgotten.

"He never stood still, his music keep moving,"

"This is what New York is about. New York is Miles Davis,"

Now, there is a permanent reminder of that famous connection between the city and the legendary musician.

http://www.milesdavis.com/fr/node/18615

NYC BLOCK PARTY CELEBRATES OFFICIAL UNVEILING OF 'MILES DAVIS WAY' ON THE 88th BIRTHDAY OF MILES DAVIS

NEWS & PHOTO TIP FOR MONDAY, MAY 26, 2014:

“Don’t Play What’s There, Play What’s Not There”

-Miles Davis

NYC BLOCK PARTY CELEBRATES OFFICIAL UNVEILING OF “MILES DAVIS WAY” ON 77TH STREET ON THE BIRTHDAY OF MILES DAVIS

WHO: Cheryl Davis (daughter of Miles), Erin Davis (son of Miles) and Vince Wilburn, Jr. (nephew of Miles), representing Miles Davis Properties, LLC and special guests.

WHAT: NYC Block Party to celebrate official unveiling of “Miles Davis Way” on the birthday of globally renowned musician Miles Davis, a major cultural innovator and originator, who changed the course of music five times. Mayor Bloomberg signed a bill to rename West 77th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Ave as “Miles Davis Way” in recognition of the legendary trumpeter, who has become synonymous with New York City. The Far West 77th Street Block Association is sponsoring the event to honor and memorialize the iconic genius’s long tenure on the street, which included regular interaction with the community.

Jazz legends such as Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey and Tony Williams (who rented an apartment in Miles’ building) used to drop by the neighborhood all the time. The West 77th Street location is where Davis created the music for such celebrated albums as Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew.

Vince Wilburn, Jr., nephew of Miles, also joined the rehearsals there and played drums on five Davis albums including Man With The Horn.

“It’s a great honor for my uncle,” says Wilburn Jr., adding “The family is very excited about Miles Davis Way and thanks the community for all of their support.”

Fans and well-wishers can show their support by getting the tweet out @milesdavis and including #MilesDavisWay in their posts, and by leaving comments at Facebook.com/MilesDavis. For updated news, please visit the official Miles Davis website at www.milesdavis.com.

WHERE: 312 77th Street (between Riverside Drive & West End Ave)

Free & Open to the Public

WHEN: 12 NOON – 2:00 P.M.

12:30 p.m. Official Unveiling

Onsite Interview availability and photo opportunities with RSVP

COMMENTS: Davis has long been noted for his restless artistry, which played into his changing the course of music five times, his continued status as a fashion icon, and his globally recognized artworks, which most recently have been featured in Paris, Brazil, Montreal and Napa to outstanding acclaim.

A quintessential Renaissance Man, Davis continues to break records as the U.S. Postal Service's most successful and fastest-selling iconic stamp in recent years, with more than 23 million sold to date.

The spotlight currently is on Miles Davis with the recent announcement of his biopic going into production this June, starring Don Cheadle, Ewan McGregor and Zoe Saldana.

In conjunction with the official unveiling of Miles Davis Way, Rock Paper Photo in collaboration with the Miles Davis Estate, will release an exclusive line of artwork on May 20, featuring the legendary musician. The line will include rare and iconic limited-edition photographs; fine art reproductions of paintings and drawings by the artist; and graphic designs inspired by the imagery and typography of classic Miles Davis album art, available in contemporary materials such as brushed aluminum and premium wood. For more information, please visit http://www.rockpaperphoto.com/miles-davis

MILES AT THE FILLMORE – Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3 – a critically acclaimed 4-CD box set is also now available, presenting four nights of historic performances at legendary Fillmore East in New York, in their complete form for the first time. Additionally, over two hours of previously unissued music, including bonus tracks that were recorded at Fillmore West.

“Don’t Play What’s There, Play What’s Not There”

-Miles Davis

NYC BLOCK PARTY CELEBRATES OFFICIAL UNVEILING OF “MILES DAVIS WAY” ON 77TH STREET ON THE BIRTHDAY OF MILES DAVIS

WHO: Cheryl Davis (daughter of Miles), Erin Davis (son of Miles) and Vince Wilburn, Jr. (nephew of Miles), representing Miles Davis Properties, LLC and special guests.

WHAT: NYC Block Party to celebrate official unveiling of “Miles Davis Way” on the birthday of globally renowned musician Miles Davis, a major cultural innovator and originator, who changed the course of music five times. Mayor Bloomberg signed a bill to rename West 77th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Ave as “Miles Davis Way” in recognition of the legendary trumpeter, who has become synonymous with New York City. The Far West 77th Street Block Association is sponsoring the event to honor and memorialize the iconic genius’s long tenure on the street, which included regular interaction with the community.

Jazz legends such as Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey and Tony Williams (who rented an apartment in Miles’ building) used to drop by the neighborhood all the time. The West 77th Street location is where Davis created the music for such celebrated albums as Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew.

Vince Wilburn, Jr., nephew of Miles, also joined the rehearsals there and played drums on five Davis albums including Man With The Horn.

“It’s a great honor for my uncle,” says Wilburn Jr., adding “The family is very excited about Miles Davis Way and thanks the community for all of their support.”

Fans and well-wishers can show their support by getting the tweet out @milesdavis and including #MilesDavisWay in their posts, and by leaving comments at Facebook.com/MilesDavis. For updated news, please visit the official Miles Davis website at www.milesdavis.com.

WHERE: 312 77th Street (between Riverside Drive & West End Ave)

Free & Open to the Public

WHEN: 12 NOON – 2:00 P.M.

12:30 p.m. Official Unveiling

Onsite Interview availability and photo opportunities with RSVP

COMMENTS: Davis has long been noted for his restless artistry, which played into his changing the course of music five times, his continued status as a fashion icon, and his globally recognized artworks, which most recently have been featured in Paris, Brazil, Montreal and Napa to outstanding acclaim.

A quintessential Renaissance Man, Davis continues to break records as the U.S. Postal Service's most successful and fastest-selling iconic stamp in recent years, with more than 23 million sold to date.

The spotlight currently is on Miles Davis with the recent announcement of his biopic going into production this June, starring Don Cheadle, Ewan McGregor and Zoe Saldana.

In conjunction with the official unveiling of Miles Davis Way, Rock Paper Photo in collaboration with the Miles Davis Estate, will release an exclusive line of artwork on May 20, featuring the legendary musician. The line will include rare and iconic limited-edition photographs; fine art reproductions of paintings and drawings by the artist; and graphic designs inspired by the imagery and typography of classic Miles Davis album art, available in contemporary materials such as brushed aluminum and premium wood. For more information, please visit http://www.rockpaperphoto.com/miles-davis

MILES AT THE FILLMORE – Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3 – a critically acclaimed 4-CD box set is also now available, presenting four nights of historic performances at legendary Fillmore East in New York, in their complete form for the first time. Additionally, over two hours of previously unissued music, including bonus tracks that were recorded at Fillmore West.

http://www.brooklynvegan.com/archives/2014/05/block_on_w_77th.html

Part of W 77th St. in NYC being renamed 'Miles Davis Way'; opening block party happening on Memorial Day

In honor of the legendary jazz musician, West 77th St. in Manhattan between Riverside Dr. and West End Ave. is being renamed Miles Davis Way and to celebrate there will be a block party this Monday (5/26, aka Memorial Day) from noon to 2 PM which is free and open to the public. The press release reads:

Mayor Bloomberg signed a bill to rename West 77th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Ave as "Miles Davis Way" in recognition of the legendary trumpeter, who has become synonymous with New York City. The Far West 77th Street Block Association is sponsoring the event to honor and memorialize the iconic genius's long tenure on the street, which included regular interaction with the community.

Jazz legends such as Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey and Tony Williams (who rented an apartment in Miles' building) used to drop by the neighborhood all the time. The West 77th Street location is where Davis created the music for such celebrated albums as Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew.

Vince Wilburn, Jr., nephew of Miles, also joined the rehearsals there and played drums on five Davis albums including Man With The Horn.

"It's a great honor for my uncle," says Wilburn Jr., adding "The family is very excited about Miles Davis Way and thanks the community for all of their support."

There's also a new line of Miles Davis artwork and photographs available from Rock Paper Photo and Miles' new live album, Miles at the Fillmore - Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3 is out now.

"It's a great honor for my uncle," says Wilburn Jr., adding "The family is very excited about Miles Davis Way and thanks the community for all of their support."

There's also a new line of Miles Davis artwork and photographs available from Rock Paper Photo and Miles' new live album, Miles at the Fillmore - Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3 is out now.

Miles Davis Way Unveiled in New York City

The legendary jazz artist is celebrated in his old neighborhood.

BY: GREG THOMAS

May 27 2014

The Root

On May 26, the day that would have been his 88th birthday, the iconic trumpeter Miles Davis was honored in New York City with the unveiling of a street, Miles Davis Way, on the West 77th Street block where he lived in Manhattan from the late 1950s to the mid-1980s. “The contribution he made to music, especially when he lived on that street, was immeasurable; some of the greatest music of all time,” says Quincy Troupe, writer of Miles: The Autobiography.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer supported the effort for recognition of Davis on the Upper West Side since the time she was a City Council member representing the area. “Mr. Davis lived in our community when he was writing his most prolific music,” she says. “The people in the neighborhood didn’t forget. They really advocated.”

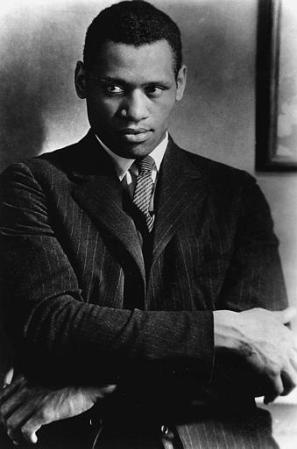

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, Miles Davis was central to major currents of stylistic development in jazz. A leader of leaders, he mentored many of the young musicians who themselves became great leaders in jazz. He was what collaborator Gil Evans (“Sketches of Spain,” “Porgy and Bess”), in the documentary Miles Ahead, called a sound innovator who changed the sound of trumpet for the first time since Louis Armstrong.

Miles apprenticed with Charlie Parker playing bebop, began experimenting with pastel sound forms with the “cool school” as a journeyman, and swung into his own leadership and mastery in the Kind of Blue period (1955-1961), resulting in the first great Miles Davis Quintet/Sextet—with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones or Jimmy Cobb and Wynton Kelley (and Red Garland or Bill Evans).

The second great quintet in the 1960s (with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, and Tony Williams) integrated elements of bebop and hard bop with their own take on avant-garde, free jazz experiments in the 1960s. In the late 60s and beyond Davis ventured new vistas, embracing a mélange of influences, incorporating electronic music, pop, rock, “Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Michael Jackson, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Paul Buckmaster,” recalls Troupe.

The person most responsible for naming West 77th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue Miles Davis Way was Shirley Zafirau, a longtime neighbor. Drummer Vincent Wilburn, nephew to Davis, says that she’s a “hero” to the Davis family. Zafirau is an avid jazz fan who, after becoming a tour guide, realized that other musical icons such as Duke Ellington and Chico O’Farrill had streets named after them but Davis didn’t. For the past five years she’s been fighting for Davis’ recognition in the neighborhood.

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2008/02/miles-davis-new-revolution-in-sound.html

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES:

(Originally posted on February 23, 2008):

Saturday, February 23, 2008

MILES DAVIS: A NEW REVOLUTION IN SOUND

by Kofi Natambu

“That period between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s was an era in which the resources of Jazz were being consolidated and refined and the range of its sources broadened. Some of the Jazz of this period reached across class and age lines and unified black audiences. Young people could see this music as “bad” in much the same sense that James Brown used the word, and older black people could see its links to black tradition.”

The legendary jazz artist is celebrated in his old neighborhood.

BY: GREG THOMAS

May 27 2014

The Root

On May 26, the day that would have been his 88th birthday, the iconic trumpeter Miles Davis was honored in New York City with the unveiling of a street, Miles Davis Way, on the West 77th Street block where he lived in Manhattan from the late 1950s to the mid-1980s. “The contribution he made to music, especially when he lived on that street, was immeasurable; some of the greatest music of all time,” says Quincy Troupe, writer of Miles: The Autobiography.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer supported the effort for recognition of Davis on the Upper West Side since the time she was a City Council member representing the area. “Mr. Davis lived in our community when he was writing his most prolific music,” she says. “The people in the neighborhood didn’t forget. They really advocated.”

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, Miles Davis was central to major currents of stylistic development in jazz. A leader of leaders, he mentored many of the young musicians who themselves became great leaders in jazz. He was what collaborator Gil Evans (“Sketches of Spain,” “Porgy and Bess”), in the documentary Miles Ahead, called a sound innovator who changed the sound of trumpet for the first time since Louis Armstrong.

Miles apprenticed with Charlie Parker playing bebop, began experimenting with pastel sound forms with the “cool school” as a journeyman, and swung into his own leadership and mastery in the Kind of Blue period (1955-1961), resulting in the first great Miles Davis Quintet/Sextet—with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones or Jimmy Cobb and Wynton Kelley (and Red Garland or Bill Evans).

The second great quintet in the 1960s (with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, and Tony Williams) integrated elements of bebop and hard bop with their own take on avant-garde, free jazz experiments in the 1960s. In the late 60s and beyond Davis ventured new vistas, embracing a mélange of influences, incorporating electronic music, pop, rock, “Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Michael Jackson, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Paul Buckmaster,” recalls Troupe.

The person most responsible for naming West 77th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue Miles Davis Way was Shirley Zafirau, a longtime neighbor. Drummer Vincent Wilburn, nephew to Davis, says that she’s a “hero” to the Davis family. Zafirau is an avid jazz fan who, after becoming a tour guide, realized that other musical icons such as Duke Ellington and Chico O’Farrill had streets named after them but Davis didn’t. For the past five years she’s been fighting for Davis’ recognition in the neighborhood.

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2008/02/miles-davis-new-revolution-in-sound.html

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES:

(Originally posted on February 23, 2008):

Saturday, February 23, 2008

MILES DAVIS: A NEW REVOLUTION IN SOUND

by Kofi Natambu

“That period between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s was an era in which the resources of Jazz were being consolidated and refined and the range of its sources broadened. Some of the Jazz of this period reached across class and age lines and unified black audiences. Young people could see this music as “bad” in much the same sense that James Brown used the word, and older black people could see its links to black tradition.”

--John Szwed

To the yang of ‘hard bop’ Davis brought stillness, melodic beauty, and understatement; to the yin of ‘cool’ he brought rich sonority, blues feeling, and an enriched rhythmic capacity that moved beyond swing to funk. By refusing to color-code either his music or his audience, Davis rose at the end of the 1950s to the summit of artistic excellence.”

--Marsha Bayles

“What is there to say about the instrument? It’s my voice—that’s all it is…”

--Miles Davis

On July 17, 1955 at the second annual Newport Jazz Festival Davis was literally invited at the last minute to join a group of prominent Jazz musicians in a staged twenty minute jam session that had been organized by the Festival’s famed music director, impresario, and promoter George Wein as part as an “opening act” for the then highly popular white headliner Dave Brubeck. Scheduled merely as a quick programming lead-in to stage changes between featured performances by the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ), the Count Basie and Duke Ellington Orchestras, Lester Young, and Brubeck, nothing special was planned in advance for this short set which, like most jam sessions, was completely improvised by the musicians performing onstage. Davis was then the least well known musician in the assembled group which was made up of Thelonious Monk, individuals from the MJQ, and other individual members of various groups playing in the festival. Wein just happened to be a big fan of Davis and added him because he was “a melodic bebopper” and a player who, in Wein’s view, could reach a larger audience than most other musicians because of the haunting romantic lyricism and melodic richness of his style. Wein’s insight turned out to be prophetic. Despite the fact that most of the mainstream audience on hand had only a vague idea of who Davis was, he was a standout sensation in the jam session and his searing performance was one of the most talked about highlights of the festival. Appearing in an elegant white seersucker sport coat and a small black bow tie, thus already demonstrating the sleek, sharp sartorial style that quickly because his trademark (and led to his eventual appearance on the covers of many fashion magazines in the U.S., Europe, and Asia), Davis captivated the festival throng with haunting, dynamic solos and brilliant ensemble playing on both slow ballads and intensely uptempo quicksilver tunes alike. Taking complete command of the setting with his understated elegance and relaxed yet naturally dramatic stage presence, the handsome and charismatic Davis breezed through two famous and musically daunting compositions by Thelonious Monk (“Hackensack” and “Round Midnight”), and then ended his part of the program by playing an impassioned bluesy solo on a well-known Charlie Parker composition entitled “Now is the Time.” which Davis had originally recorded with Bird in 1945 That cinched it. He was a hit. Miles had returned from almost complete oblivion to becoming a much talked about and heralded star seemingly overnight (of course this personal and professional recognition had been over a decade in the making). After a long, arduous struggle as both an artist and individual that began in his hometown of East St. Louis, Illinois when he started to play trumpet at the age of 13 in 1939, Miles Davis had finally “arrived.” For the first time since 1950 he was completely clean and off drugs. No longer addicted Miles now played with a bravura command and creative clarity that he had been fervently searching for well before he had become addicted to heroin. It would be the beginning of many more incredible triumphs and struggles that would catapult the fiery young trumpet player to the very pinnacle of his profession and global fame and wealth over the next ten years.

On hand for that historical summer concert in Newport, RI. was George Avakian a young music producer from the large corporate recording company called Columbia (now Sony). Miles had been after Avakian for over five years trying to get a recording contract with Columbia which was then the largest and most successful music company in the United States, but Avakian had been cautiously waiting for a sign that Davis had conquered his personal problems and was ready to commit fulltime to his music. Clearly Miles was now ready. Avakian’s brother Aram whispered to George during the concert that he should sign Davis now, before he became a big hit and signed with a rival company instead. Miles himself was nonplussed about the critical acclaim he was now receiving, wondered what the fuss was all about and maintained that he was simply playing like he always had. While there was some truth to this assertion it was also clear that Miles highly disciplined demeanor, new responsible attitude, and impeccable playing now indicated his intent on making a new commitment to living a life strictly devoted to his art. Avakian and Columbia representatives met with Davis two days later on July 19, 1955 to sign him to a new contract with the understanding that Davis would first fulfill the remainder of his contract with the Prestige label by doing a series of recordings in the fall of 1955 and the spring and fall of 1956 while at the same time making his first recordings with Columbia that would not be released until after the public appearance of the Prestige sessions. These small label recordings for Prestige would immediately become famously known as the “missing g” sessions (so-called for the dropping of the letter ‘g’ in the titles of these records, (e.g. Walkin’, Workin’, Cookin’, Steamin’, and Relaxin’). Featuring Miles’ first great, legendary Quintet this young aggregation (the oldest member of the group was 33 years old) featured then relative unknowns John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. From the very beginning this group and Miles himself would remake Jazz history and become an innovative and protean musical harbinger of great changes to come in the music as well as the general culture. As with all great musicians the creative basis and structural foundation of this new cultural and aesthetic intervention would be Miles unique, highly individual sound on his chosen instrument, the trumpet.His was a sound that embraced the entire history of Jazz trumpet in its meticulous attention to the demanding technical and physical requirements of the instrument yet also sought a creative and expressive approach that openly allowed for more subtle emotional nuances to emerge from his playing than were common traditionally on trumpet. Miles brought a highly burnished lyricism that was both deeply introspective and fiercely driving all at once. A major characteristic of Davis’s playing was a new and different way of phrasing in which a major emphasis and focus on the relationship of space to tempo and melody (and the intervals between notes) became the hallmark of his style. In the process Davis dramatically redefined and expanded the expressive and creative range of the tonal palette and instrumental timbre of the trumpet. By shifting the traditional emphasis from the heraldic and bravura functions of the instrument to a more diverse and expansive range of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic ideas Miles was able to openly express the anguished conflict, sardonic irony, restless desire for cultural and social change, and questing existential/psychological anxiety of the modern age. This intense attention to the broader expressive possibilities of both musical improvisation and composition also turned the feverish search for new forms and methods that characterized the era into a parallel personal quest for discovering a wider range of emotional and psychological contexts in which to play. The sonic exploration of the complexities and ambiguities of joy, rage, love, and melancholia was a major hallmark of Miles’s style. Central to Miles’s vision and sensibility was an equally exhilarating appreciation for the balanced expressive and intellectual relationship between relaxation and tension in his music. By focusing specifically on the spatial and rhythmic dimensions of melodic invention Miles developed musical methods that called for, and often resulted in, a precise minimalist approach to playing in which each note (or corresponding chord) carried an implied reference to every other note or chord in a particular sequence of musical phrases. Through a technical command of breath control and timbral dynamics induced by his embouchure and unorthodox fingering of valves Miles could maintain or manipulate tonal pitch at the softest or loudest volumes. By creating stark dialectical contrasts in his sound through alternately attacking, slurring, syncopating or manipulating long tones in particular ensemble or orchestral settings ( a technical device Miles often referred to as “contrary motion." Miles was able to convey great feeling and emotion through an economy of phrasing and musical rests. This rapt attention to allowing space or the silence between note intervals to dramatically assert itself as much or more as the notes themselves created great anticipation in his audience as to how these tensions would be resolved (or not). In this respect the insightful observation by the French Jazz critic and music historian Andre Hodeir that Miles’s sound tends toward a discovery of ecstasy is a rather apt description of Davis’s expressive approach. What emerged from Miles’s intensely comprehensive investigation of the creative possibilities of the instrument was a deep and lifelong appreciation for the tonal, sonic, and textural dimensions of playing and composing music. These aesthetic concerns as well as Miles’s innovative creative solutions to the rigorous challenges of improvisational and composed ensemble structures alike in the modern Jazz tradition soon revolutionized all of American music, and made Davis one of the leading and most influential musician-composers in the world during the last half of the 20th century. However Davis’s widespread social, cultural, and political influence didn’t end there—especially in the black community. Davis also quickly became a social and cultural avatar whose highly personal combination of cool reserve, fiery defiance, detached alienation, intellectual independence, and striking stylistic innovation in everything from clothes to speech embodied, and largely defined for many, the ethos of ‘hip’ that pervaded the black Jazz world of the 1950s and early 1960s. But Miles, while remaining very hip, at the same time also lived and worked far beyond the insular world of hipsterism and avant-garde bohemia. He was unique in that his stance was simultaneously existentialist and engaged. As many observers, fans, scholars, friends, and critics have noted Miles became in many ways what the critic Garry Giddins called “the representative black artist.” of his era. John Szwed, Yale University music professor and author of a biography in 2002 of Miles entitled So What: The Life of Miles Davis speaks for a couple generations of writers, fans, artists and musicians when he states that by the late ‘50s, early 1960s:

“Miles was becoming the coin of the realm, cock of the walk, good copy for the tabloids, and inspiration for literary imagination. Allusions to him could turn up anywhere…Tributes to him sprang up in poems by Langston Hughes (“Trumpet Player: 52nd Street”), and Gregory Corso…Young people ostentatiously carried his albums to parties and sought out his clothing in the best men’s stores. In person, his every action was observed and read for meaning…A discourse developed around him, one that bore inordinate weight in matters of race—Miles stories—narratives about his inner drives, his demons, his pain, and his ambition. Invariably, his stories climaxed with a short comment, crushingly delivered in a husky imitation of the man’s voice, capped by some obscenity…He was the man.”

Among many black people Davis’s outspoken, defiant social stance and hip, charismatic aura signified a profound shift in cultural values and attitudes in the national black community that also had a lasting political significance and influence. This was especially true for the emerging adolescent youth and radical young adults of the era whose overt displays of rebellion and defiance of white society’s racism and repression were becoming pervasive with the rise of the Civil Rights, and later Black Power, movements. Miles quickly became a major symbol of this modern revolutionary spirit in African American culture and was seen by many as an important artistic leader in this struggle and its widespread social and political demands for respect, justice, equality, and freedom for African Americans that marked the period. Thus it is not surprising that many of the various musical aesthetic(s) that Davis devised and expressed during the late ‘50s and throughout the ‘60s consciously sought to advance specifically new ideas about the structural, formal, and expressive dimensions of the modernist tradition in contemporary Jazz music. These changes would openly challenge many of the orthodoxies of this tradition in terms of both form and content while at the same time asserting a radically different set of ideological and aesthetic values about the intellectual and cultural worth, use, and intent of the music that in attitude and style sought to resist or go beyond standard notions of both high art and commercial popular culture. Simultaneously however, Davis sought to consciously establish an even more socially intimate relationship with his black audience (and especially its youthful members) that would embody and hopefully expand Davis’s views on the broad necessity for deeply rooted political and cultural change within the African American community and the U.S. as a whole.

In the quest to critique many of the philosophical assumptions governing conventional modernist discourse in art while still retaining a fundamental aesthetic connection to other important aspects and principles of modernism—especially those having to do with with the continuous necessity of creative change and revision—Davis epitomized the ‘progressive’ African American Jazz musician’s desire to use black vernacular sources, ideas, and values to engage these modernist traditions and principles on his/her own independent social, cultural, and intellectual terms. In such major recordings from the 1957-1967 period as his orchestral masterpieces Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and Sketches of Spain (made in collaboration with his longtime friend and colleague, the white composor and arranger Gil Evans), and his equally significant and highly influential small group Quintet and Sextet recordings, Milestones, Kind of Blue, Live at the Blackhawk, My Funny Valentine, Four & More, E.S.P., Miles Smiles, Live in Berlin, Live in Tokyo, Live at the Plugged Nickel, and Nefertiti, Davis was at the forefront of those African American artists of the period in all the arts who were feverishly looking for and often finding fresh, new modes of pursuing aesthetic innovation and social change. By dialectically synthesizing and extending ideas, strategies, methods, and structures culled from such disparate sources as 20th century classical music, the blues, R & B, and many different stylistic forms from the Jazz tradition (i.e. Swing, Bebop, ‘Cool’ and ‘Hard Bop’ etc.)—many of which Davis himself had played a pivotal role in developing and popularizing—Miles helped bring about a new creative synthesis of modern and vernacular expressions that greatly changed our perceptions of what American music was and could be.